Cycle 2

Posted: December 9, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »Exploring the “D” in DEMS.

For Cycle 2 I wanted to take some of the lessons learned from Cycle 1 and further develop them. (My Cycle 1 is the “Order of the Veiled Compass” project) My tendency is to focus on the building and engineering of projects and less so on the “devising”, this was an opportunity to take a deeper dive in to the part of DEMS I typically spend the least time on. My presentation was a simple PowerPoint slide show that explored how people interact with technology, not exactly riveting website material, so this post will present the information is , hopefully, a more interesting manner. The original presentation can be found here https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1qVqp1khbiujVJ4hC5ohTrTZNLGGDL-AK/edit?usp=drive_link&ouid=106949091808183906482&rtpof=true&sd=true

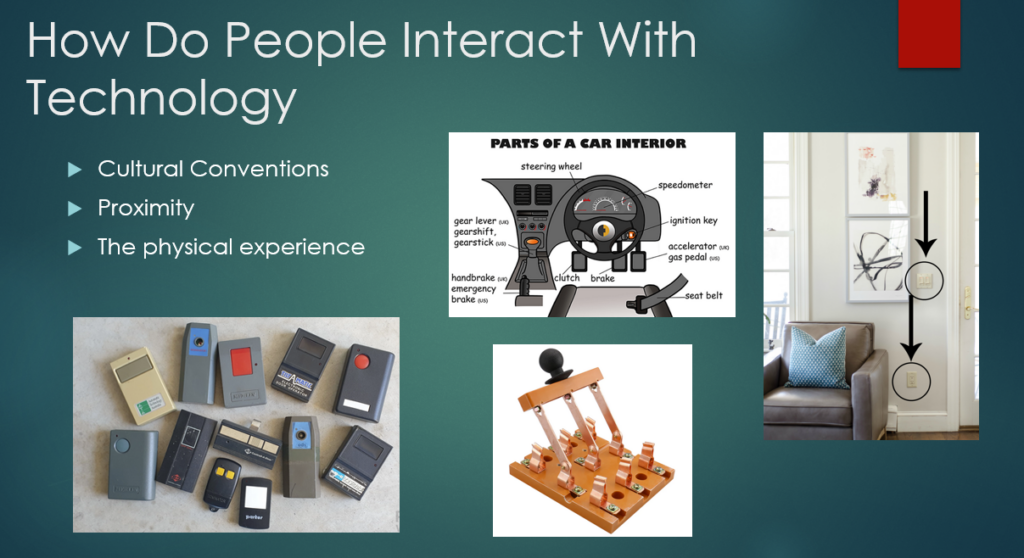

How do people interact with technology in both everyday life and in regards to an Experiential Media System? I identified what I believe are three key factors to our interactions, Cultural Conventions, Proximity, and the Physical Experience.

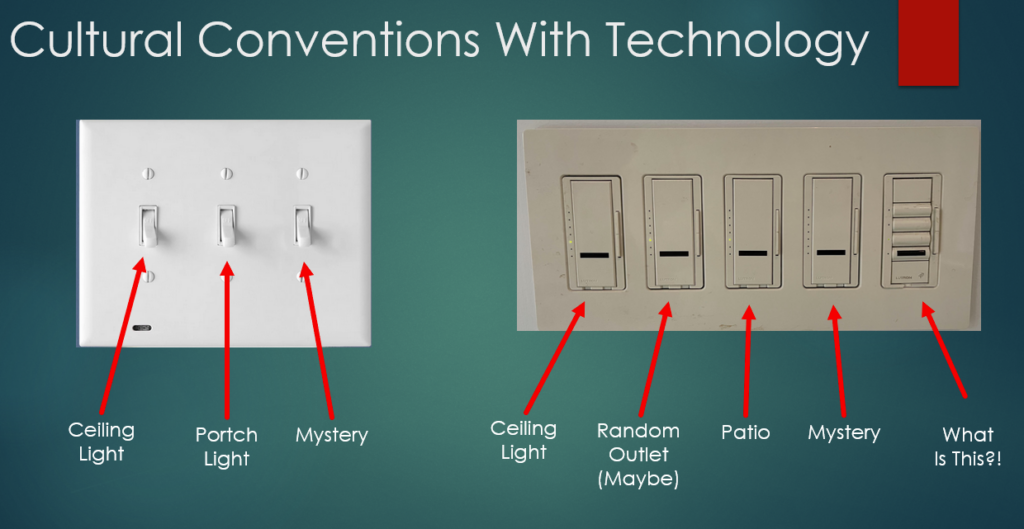

Since this post is on a website I can make several inferences about you (the reader). First, you have access to electricity and an internet connection. You can be anywhere on the earth, assuming you are indoors and there is a light switch, that switch is located within a foot or so of the doorway. If you have been a passenger in some sort of vehicle, that machine had a break peddle on the left and an accelerator on the right, with some type of switch within easy reach of the steering mechanism to activate turn signals. Cars, busses, trucks, etc… all share a similar technical language. An argument can certainly be made that many of these conventions are the result of Edison Electric, Westinghouse, and similar companies developing these technologies and distributing them, but the road to the present day is not as straight forward as it seams.

For example, I am 99.9999% confident that you can not drive a Model-T Ford. Looking at the above photo there are many familiar controls (assuming you can drive a stick). With the exception of the steering wheel and the gear shift lever, almost none of the familiar looking controls do what you think they do. It took awhile, but eventually the automakers of the world settled on a control layout that allows anyone who knows how to drive a car drive almost all other cars.

The key take away form all of this is that we are all conditioned to expect certain technologies to work is specific ways. Lights are turned on by a stitch by the door or a switch on the light itself. All cars have an accelerator and a break. None of us need a manual to use a faucet or garden hose, regardless of where on earth we find one. Any sink with a garbage disposal will have a control switch within a few feet of it.

We interact with technology is variety of ways, for this project I focused mainly on touch. Advances in machine vision and hearing have made it possible to interact with devices via gesture and our voice, but that is a conversation for a different day.

I wanted to take a closer look into what makes a physical interaction with technology a good one. This is personal preference of course, but I am confident that there are certain aspects we can all agree upon. One is that quality matters. Imagine you press a button on a vending machine or arcade game and its a plastic piece of junk that rattles, if it lights up it probably flickers, and it makes you press it several times to be sure it did something; that’s not the best interaction with technology. Compare that to a nice solid metal toggle switch, even better if that switch has some type of safety cover on it! I don’t want to go through the steps of launching a missile to make a pot of coffee, but I do appreciate solid feeling controls on the coffee maker.

Feedback is a critical component to the physical experience. A doorbell is an excellent example of a system with ambiguous feedback. You press the doorbell. Did it work and nobody is home? Did the doorbell not ring? Unless you are inside to hear it there is no indication that it worked or not, which is frustrating. It can be very frustrating when technology doesn’t let the user know that it is working. Imagine an elevator that didn’t indicate which floor it was going to, or a telephone that was perfectly silent until answered, those would be horrible user experiences!

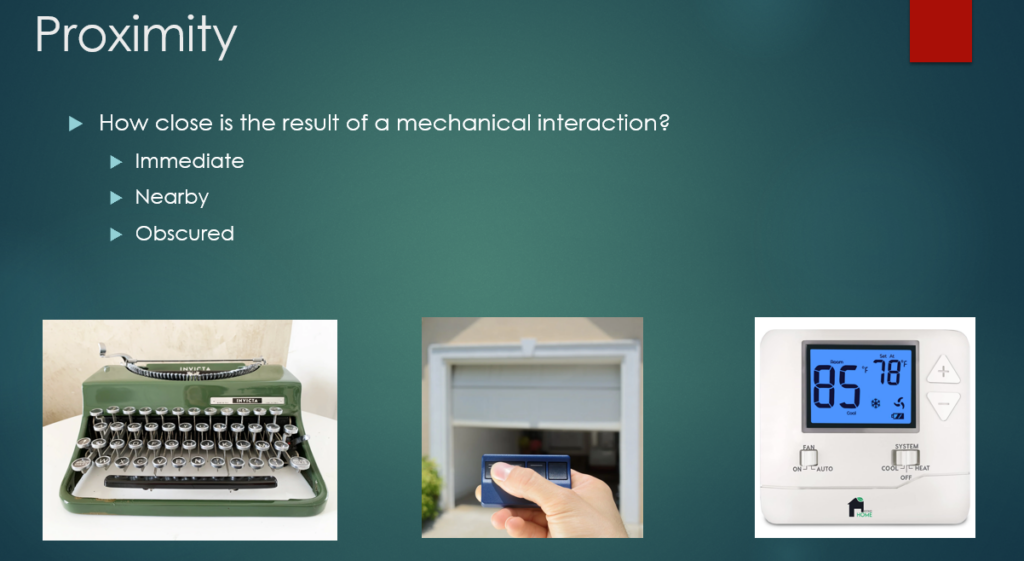

Of particular interest to me and my home DEMS project, is the idea of proximity. When a user interacts with a piece of technology, how far away is the response? Is it at the users fingertips like with a typewriter, or is the action completely obscured form the user such as a furnace controlled by a remote thermostat? Perhaps is a middle ground, remote but visible, like a garage door opener.

Building upon the idea of cultural expectations for technology, the concept of proximity helps us further describe our interactions with tech. Light switches are usually found near doorways. We enter a room, find the switch, and the light turns on. This is an example of close proximity, it is immediately obvious that the action of the user caused the technology to respond. Many of us have experienced the frustration that arises when the proximity has been increased. I know in my house there are several light switches whose function remains a mystery. My action of flipping the switch is not rewarded with a response that is immediately visible.

Lights are an example of a common piece of tech that we are accustomed to having close proximity to. The same is true with doors, television remotes, hand tools, etc… HVAC technology is usually hidden out of sight. When we adjust the thermostat the machines come to life but they are often out of sight and provide no indication that they are functioning.

All of this and DEMS.

The goal of all this is to help Devise an experiential media system. By having an understanding of the rules we all play by when it comes to technology, we can begin to play with the rules. For example, what if a light switch played a honking sound when flipped instead of turning on a light? Or what would someone do if they turned a doorknob and a door several feet away opened instead? By taking the ideas of cultural expectations, the physical experience, and proximity and playing with expectations, many new possibilities emerge.

I can think of no greater example of this that the creation of Disneyland in 1955. The gates opened on July 17 and the world of immersive entertainment changed forever. (The opening day was an absolute disaster and I encourage you to read about it!) Guests were presented with technology and experiences that didn’t exist before, the rules had rewritten.

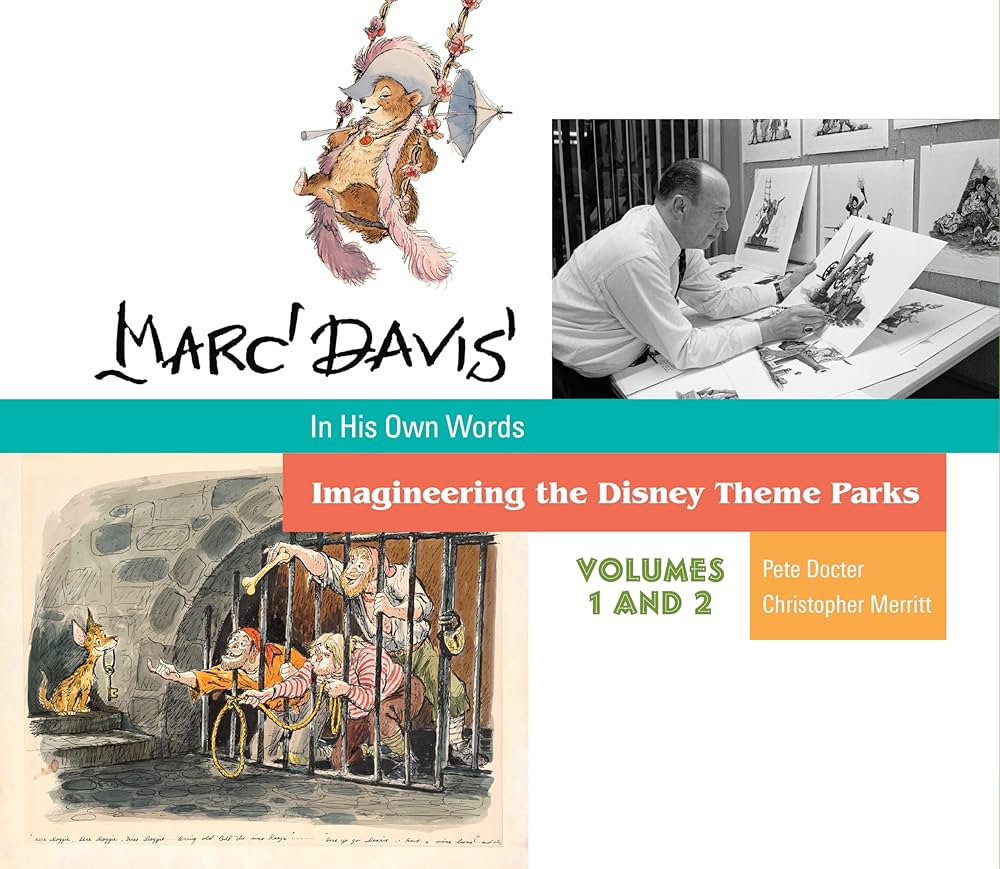

The above set of books served as a fascinating guide to the design and implementation of many attractions of the Disney parks and the 1964 Worlds Fair in New York. The goal was to sell tickets of course, but the means was by creating unique experiences that the world had never seen before. This required the invention of new technologies and concepts. One of the key problems to solve was how to get as many people as possible through the attractions as quickly as possible while also ensuring they had a good time.

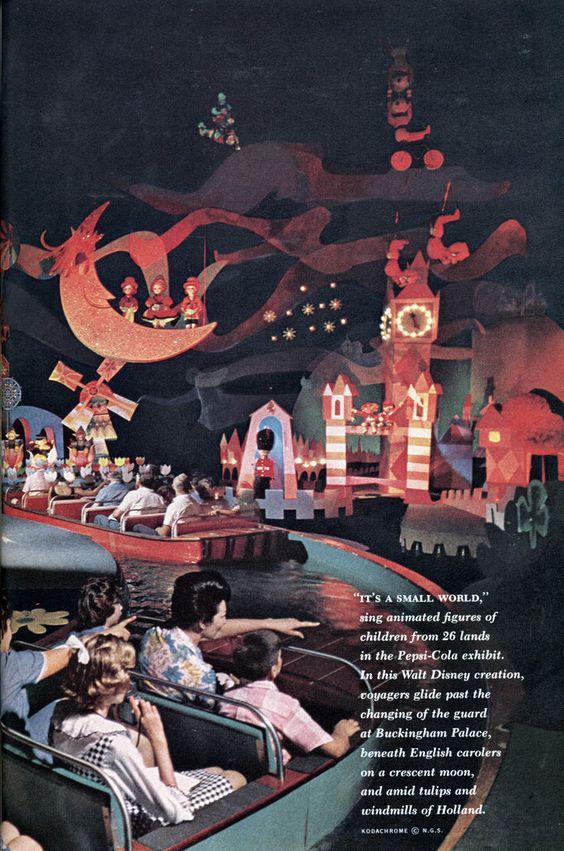

Above is “It’s a Small World” from the 1964 Worlds Fair. The ride was designed and built for the Pepsi pavilion and featured small boats for guests to ride. This allowed for a large number of people to be cycled through the attraction at a steady pace.

A better example of how technology and proximity come together is in the Jungle Cruise ride. Above is a piece of concept art for the ride by Mark Davis. The Disney team had to figure out how to tell a narrative as quickly as possible without letting the guests actually interact with anything. Guests must “keep their hands and arms inside the ride at all times” to protect them, and the attractions, from harm. By necessity the tactile experience is removed and the proximity is fixed at a middle distance. Guests also only have a few moments to observe the various scenes before they move past them. By limiting the “scenes” to simple motions and exaggerated behaviors it was possible for riders to “get” the visual gag being shown to them.

In theme parks, shrinking the proximity of the attraction to the guests can have an extreme impact. Above is the Yeti from the Expedition Everest ride at Disney’s Animal Kingdom in Orlando. It is one of the largest animations ever made, over 25′ tall, and goes from remote proximity to uncomfortably close very quickly. Anamatronics were commonplace by the time this ride came to be, they were often of the mostly static variety as seen on the Jungle Cruise or the Haunted Mansion. Here designers used proximity to terrify people. As the riders raced past the yeti on a roller coaster the enormous machine would lunge and swipe at the riders, just barley missing them (from the riders perspective). This never before seen behavior terrified people and was a huge success! Unfortunately the technology at the time was not up to the task and the animatronic has been mostly static for years due to maintenance issues.

Historic DEMS

Another source of inspiration for Cycle 2 was the work, “Stained Glass” by Sonia Hilliday and Laure Lushington. They explore the history and styles of stained glass through the ages focusing mainly on Christian cathedrals. Disney may have invented theme park, but perhaps it was the church that created DEMS? (What counts as the first DEMS is certainly up for debate, but here I will cherry pick the cathedrals as a prime example of a DEMS.)

Above is Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, built 1241-1248. This is an outstanding example of a DEMS that takes into consideration proximity, the tactile experience, and cultural expectations. But first a little stage setting. Imagine you are visiting Paris in the 13th century, you have no idea what electricity is, or anything about technology more complex than a shovel, and you walk into that cathedral. It is the technological equivalent to a modern US Navy super-carrier. Every detail has been thought about and addressed. The smell of incense lingers in the air, a choir sings from an alcove, and everywhere is brilliant light. I imagine the experience would be like being hit with a metaphorical sledge hammer.

The physical experience is top notch in every respect. There are no cheap materials in this place, everything is solid wood, iron, and stone. The cultural part of the interaction is immense but I will not dive into that here. But what about proximity? Perhaps we are well to do and can get seats close to the altar for mass, the less well off sit further away. The monks and sisters are cloistered behind screens, preventing us from getting too close. What are we trying to gain proximity to in the first place? Proximity to the divine is the goal here. By utilizing the senses and cultural expectations the cathedral brings us closer to heaven. Proximity is not limited to physical distance in a DEMS.

Lets take a U-turn from the DEMS of the cathedral and visit medieval Kyoto, Japan. Above is Saihoji Temple, also known as the moss temple. Sophie Walker writes about such places in her excellent work, “The Japanese Garden.” If you ever want to write a book about Japanese gardens there is a rule you need to follow. For every one page about plants and the act of gardening, you must first write 40 pages about the human condition and its history.

What looks like a natural arrangement of plants and rocks, is actually a meticulously crafted DEMS. Every aspect of a Japanese garden has been done with great care and thought. Every rock, every plant, or absence of plants, has been painstakingly planed out and executed with the upmost care. Like the cathedral the physical experience is top notch, all natural in this case, but we can expect stone and untreated wood in addition to the plants. The technology in the garden is hidden and deceptive. Below is a prime example of this. We see a simple path. Like the lights switch we all know how to step from stone to stone, but take a closer look. The stones are of uneven size and shape and do not lie in a straight line. To keep from tripping guests must walk slowly with care, paying careful attention to their footing. However, in the intersection there is a much larger flat stone. The designer of this path deliberately placed every stone knowing that when the guest got to the flat spot they would stop and take a better look at their surroundings. If there is a “best place” to view this area of the garden, it is form that stone. Using proximity and the careful control of what a guest can see and what is obscured is the technology at play here.

Another important concept from the Japanese garden is the simple technology of a gate. A gate is a physical barrier that dictates our access to something. Below we can see a garden path with a gate preventing access to what I presume is a tea house. Lets abstract the idea of a gate to a more metaphorical idea, lets think of gates as thresholds or transitions. In the garden, gates, either real or implied, are opportunities to transition our thoughts and emotions. The cultural purpose of these gates is to reduce our proximity to zero, we are invited to engage in self reflection. In the image below the idea is that to pass the threshold, here represented by a physical gate, the guest must leave something behind. It could be some worry, worldly desire, etc… The technology is extremely subtle, but equal in power to the cathedral.

It’s time to bring all of this together into a ACCAD5301 DEMS project.

A brief recap of Cycle 1 is in order here. My project is built around inviting guests into my home to enjoy a party. Please see my Cycle 1 project for the details. Guests arrive at the party with a clue in hand and an expectation that the event is going to be a little unusual. The intention is that each guest, or pair of guests, arrives at a specific time in order to get the full experience as intended. They ring the door bell and are welcomed into the house, which is where the fun begins.

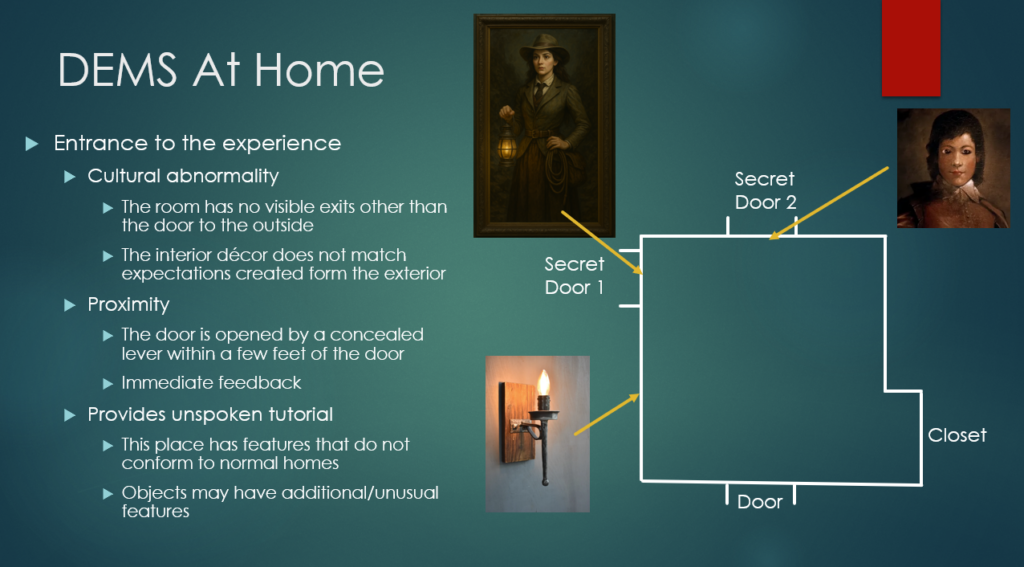

Right away I am taking the rules about how we expect technology to work and are bending them. The guests enter a room that has only one door, the entrance they came in through. A house is a technology, one that usually has more than a foyer, but that cultural norm has been broken here. Right away the guests are confronted with the reality that this place is unusual.

I do not like the idea of having hidden cameras in my home, so I will not have any. However it is still necessary to observe how the guests are managing the challenge of leaving the room. On one of the walls there is a painting of someone that has several secrets. First, the wall it is on is also a hidden door, but one that the guests are unable to open form where they are. Second, on the other side of the wall a small flap can be opened allowing someone to look through the eyes of the person in the painting. Again, this is giving a technology (the painting) properties that it shouldn’t have.

Above is a ChatGPT attempt at the room I am talking about. There are no obvious doors to leave through. However, there are several wall sconces! By solving the puzzle contained in the invitation the guests should be able to figure out that by manipulating one of the sconces the large painting (and the wall it’s on) moves asides providing access to the rest of the home.

Proximity is very important here. Guests need to learn that in this environment there are hidden mechanisms, and that objects may be capable of doing unusual things. When they perform an action the corresponding effect must be obvious. Here the act of manipulating a secret lever opens a door a few feet away, the connection is obvious. The guests should now be suspicious of every piece or art in the home!

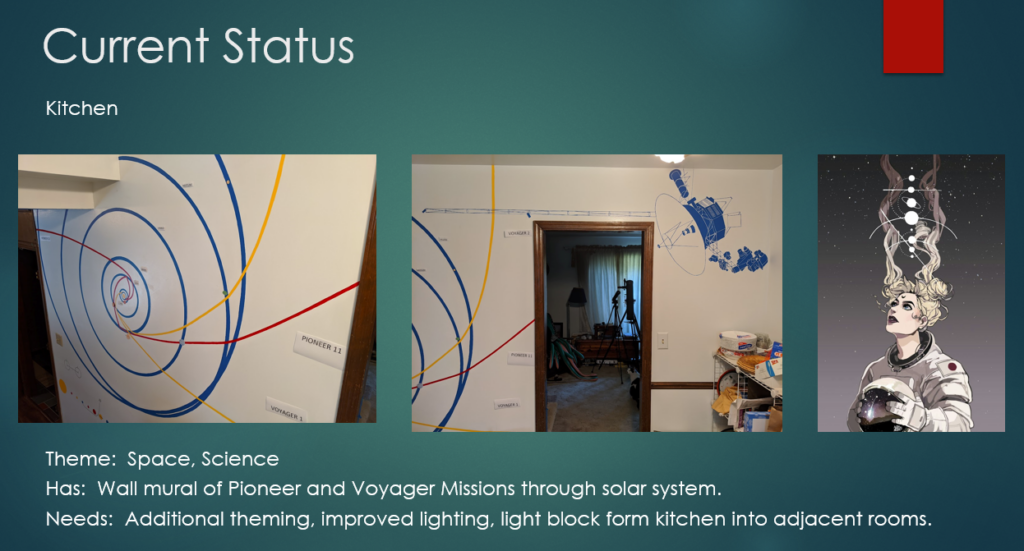

The images above are a few examples of what the rest of the home currently looks like. I am the king of unfinished projects, and there is still much work to be done. Taking inspiration from the Japanese garden designers, the act of placing a door (threshold) separating the entrance to the home and the rest of the place, creates an opportunity to dramatically effect the guest experience. This is an opportunity for a WOW moment. The first room they encounter is lit by indirect lightning on the ceiling, I am partial to the blue look but it is capable of being other colors. The walls are lined with dozens of stained glass lanterns all glowing. There is a map of the world on the ceiling with various locations highlighted via hidden fiber-optic lights. Again, this is not normal for a home, which is exactly the point. This place doesn’t follow the normal culturally agreed upon rules.

The guests meet the host of the evening, the mysterious Curator. She welcomes the guests and gives them a brief tour. She also hands them a small envelop with another puzzle to solve inside. What the guests are not aware of yet is that the home has a basement which they are unable to access, there is another secret passage. They have been handed a clue that will lead them to the means to access the basement.

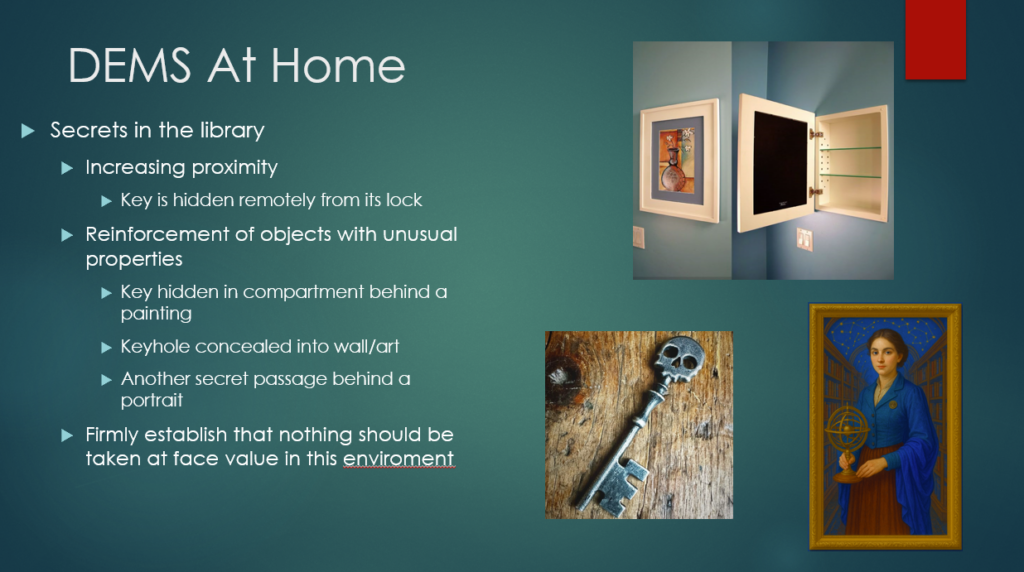

The exact puzzle is still being debated, but the first step is that the guest needs to find a key hidden in a secret compartment being a small piece of wall art. Again, this is not something that wall decor doesn’t normally do. The key itself is important. Anyone who finds a secret key to open a secret passage doesn’t want to have some ordinary house key! Oh no, that simply will not do here. The plan is to reward the guest by presenting them with something home made that is large, heavy, and ornate. The physical experience is a critical piece of this part of the DEMS.

This is where the difficulty ramps up a little. The key will have built into its design the clue as to where the lock is concealed. The example image above shows a skull key, perhaps the lock is hidden in the eye of a skull somewhere. Eventually the guest should be able to locate the hidden lock and manipulate it with the key. It is now time to increase the proximity of the action to the result. When the lock is turned, another painting slides away to reveal the access to the basement. (Yes, its the same trick as the first door, but the sliding panel takes up the least amount of space.) I want the result to be unsees from the guest. There needs to be some type of feedback to alert the guest that the lock worked, perhaps the skull could light up, or there is some type of sound that plays. There should be a little confusion though, the guest should want to look around to see what happened. When they look around they will eventually return to the library where there is now a new path to explore!

As the party progresses there will be more puzzles to solve. It will be necessary for the guests to work together to solve the mysteries, break the curses, etc… An exciting possibility arises when there are more people involved, the proximity of action to technological response can be increased. With more eyes on the look out for changes in the environment it becomes easier to bend even further the rules normally associated with technology.

I am particularly interested in puzzles that require pieces to be brought together to accomplish something. For example, suppose we have a locked treasure chest that has resisted all attempts to open. The chest arrived at the society with a letter mentioning a curse that must be broken before the treasure can be shared. Perhaps one of the guests has on them a ruby ring (they were supplied with this as part of their character) that has been in the family for generations and is said to have belonged to a famous pirate captain. Well what a coincidence, there just so happens to be a pirate skeleton in the library! (This is true, her name is Margret, and she has a fancy pirate hat.) Perhaps returning the ring to the hand of its rightful owner will break the curse?

The goal is to provide high quality props that have been given properties and abilities they shouldn’t have. By bringing these object closer together, or further apart, aka changing the proximity, something magical can happen. By intentional building in gates/thresholds, both of physical space and knowledge, it is possible to guide and manipulate guests in subtle ways that hopefully will lead to an enjoyable experience. It is a party after all.

Everyone should have a good time. The point is not to punish people for not solving the puzzles, so hints should be given as needed. Similarly, broken props/tech should be removed. This is a quality DEMS! One that shouldn’t take itself too seriously, there is plenty of room for whimsy. There defiantly needs to be a giant carnivorous plant that chomps at people when they get too close!