Pressure Project 3: Expanded Television

Posted: December 18, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »I had a lot of ideas for this pressure project but ended up going with an expanded version of my first pressure project. I thought it would be really fun to use a Makey Makey to an actual TV remote into something that can control my Isadora TV. If I used sticky notes and conductive pencil drawings, I could fake pressable buttons to change the channel and turn it on and off.

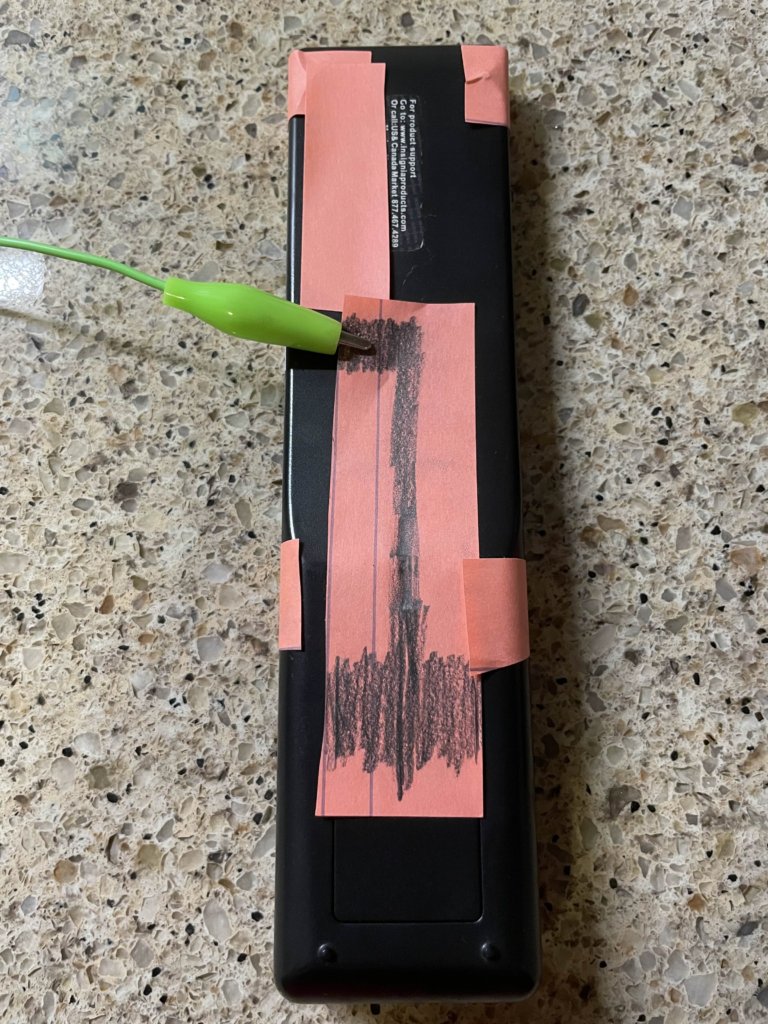

To me, the hardest part of using a Makey Makey is always finding a way to ground it all. But I had the perfect idea of how to do this on the remote: because people usually have to hold a remote in their hand when they use it, I can try to hide the ground connection on the back! See below.

This worked somewhat well but because not everyone holds a TV remote with their hand flat against the back, it may not work for all people. You could use more paper and pencil to get more possible contact points, but this got the job done.

For the front buttons, I originally also wanted the alligator clips to be on the back on the remote, but I was struggling to get a consistent connection when I tried it. I think the creases at the paper bends around to the back of the remote cause issues. I’m pretty happy with the end result, however. See below.

For Isadora, I created a new scene that was the TV turning on so that people could have the experience of both turning on and off the TV using the remote. The channel buttons also work as you would expect. The one odd behavior is that turning on the TV always starts at the same channel, unlike a real TV which remembers the last channel that it was on.

I also added several new channels, including better static, a trans pride channel 🏳️⚧️, and a channel with a secret, a warning channel, and a weird filter glitchy channel. Unfortunately, I cannot get Isadora to open on my laptop anymore! I had to downgrade my drivers to get it to work and at some point the drivers updated again. I cannot find the old drivers I used anymore! It’s a shame cause I liked the new channels I added… 🙁

The static channel just moves between 4 or so images to achieve a much better static effect than before and the trans pride channel just replaces the colors of the color bar channel with the colors of the trans flag.

The main “secret revealed” I had was a channel that started as regular static but actually had a webcam on and showed the viewers back on the TV! The picture very slowly faded in and it was almost missed, which is exactly what I wanted! I even covered the light on my laptop so that nobody would have any warning that the webcam was on.

There was also a weird glitchy filter channel that I added. This was inconsistently displayed and was very flashy sometimes but other times it looked really cool. Because of this, I added a warning channel before this channel so that anyone that can’t look at intense things could look away. When I did the presentation, it was not very glitch at all and gave a very cool effect that even used the webcam a little bit (even though the webcam wasn’t used anywhere in that scene…)

The class loved the progression of the TV for this project. One person immediate became excited when they saw the TV was back. They also like the secret being revealed as a webcam and appreciated the extra effort I put in to covering the webcam light as well. In the end, I was very satisfied with how this project turned out, I just wish I could show it…

Cycle 3: Failure and Fun!

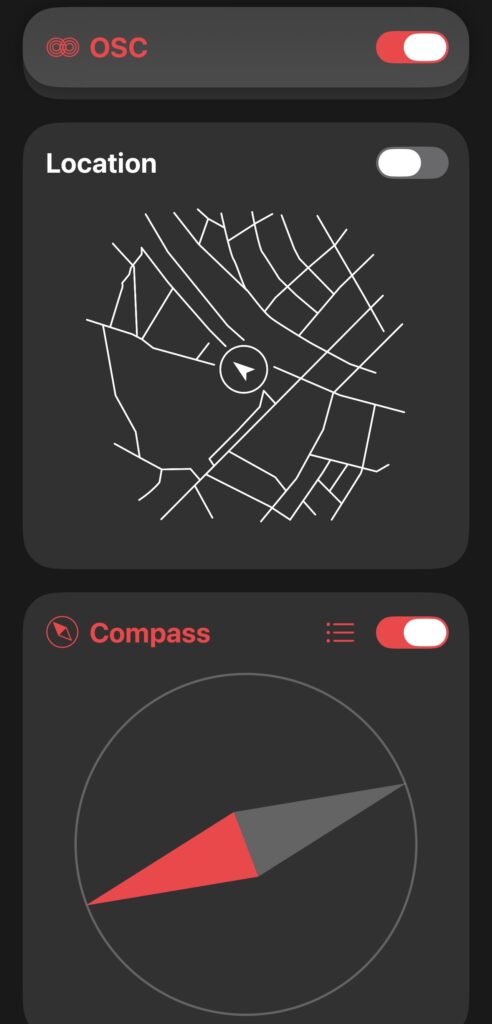

Posted: December 18, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »My plan for this cycle was simple: add phone OSC controls to the game I made in previous cycles. But this was anything but simple. The first guide I used ended up being a complete dead end! First, I used Isadora to ensure that my laptop could receive signals at all. After verifying this, I tried sending signals to Unity and nothing! I tried sending signals from Unity to Isadora and that worked(!) but wasn’t very useful… It’s possible that the guide I was following was designed for a very specific type of input which the phones from the motion lab were not giving, but I was unable to figure out a reason why. I even used Isadora to see what it was seeing as inputs and manually set the names in Unity to these signals.

After this, I took a break and worked on my capstone project class. I clearly should have been more worried about my initial struggles. I tried to get it working again at the last minute and found another guide specifically for getting phone OSC to work in Unity. I couldn’t get this to work either and I suspect this was because it was for touch OSC which I wasn’t using (and also didn’t need the type of functionality). I thought I could get it to work but I was getting tired and decided to sleep and figure it out in the morning. I set my alarm for 7 am knowing the presentation was at 2 pm (I got senioritis really bad give me a break!). So imagine my shock when I wake up, feeling rather too rested I should say, and see that it’s nearly noon! I had set my alarms for 7 pm not am…..

This was a major blow to what little motivation I had left. I knew there was no chance I could get OCS working in that time and especially no way I would get to make the physical cardboard props I was excited to create. I wanted to at least show my ideas to the class so I eventually collected myself and then quickly made a presentation to show at presentation time.

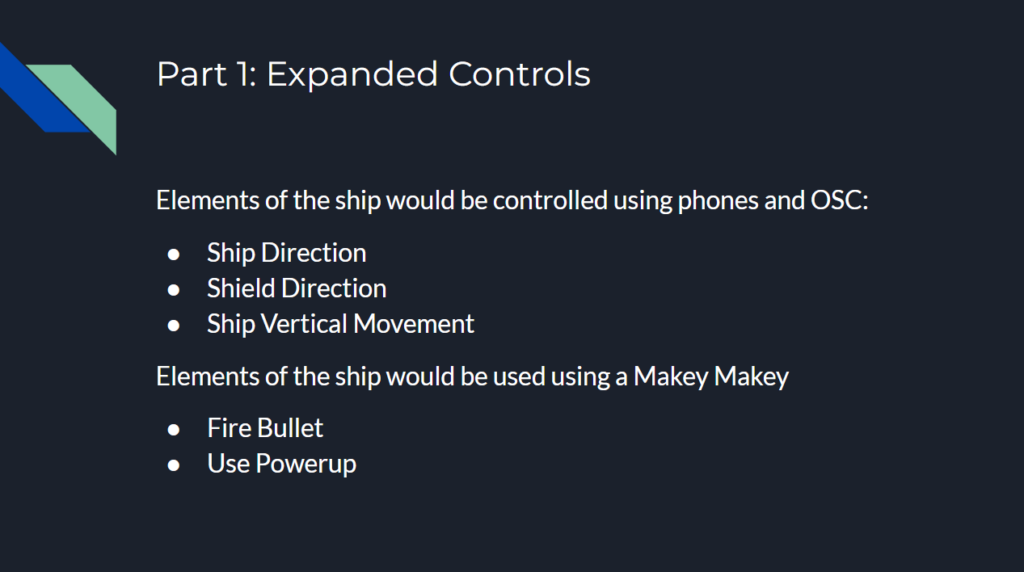

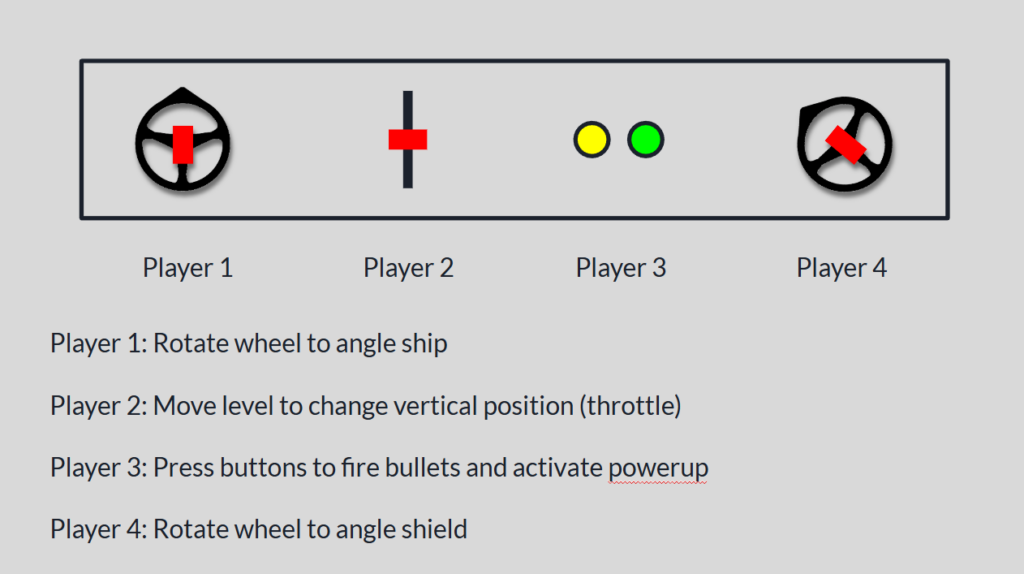

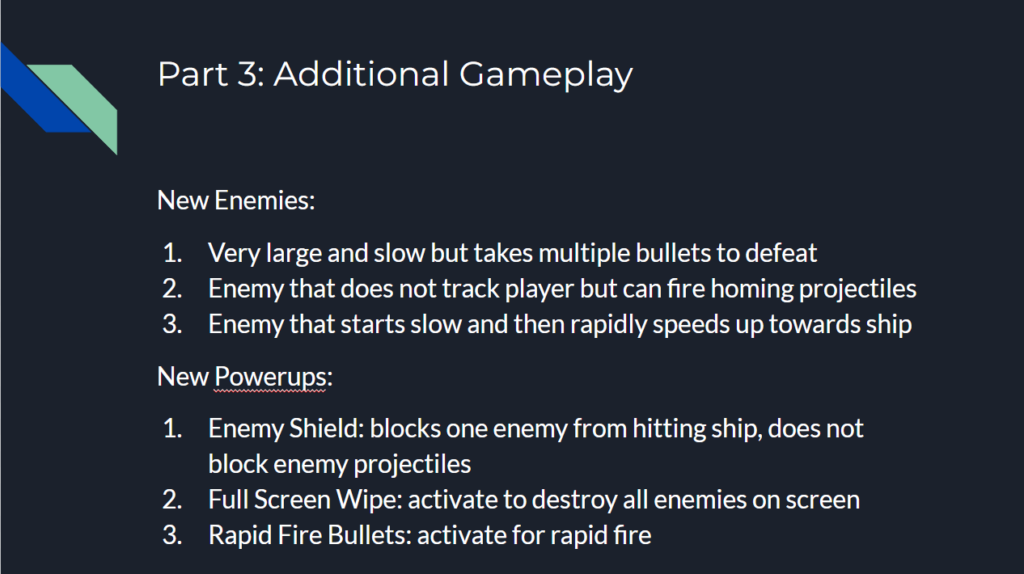

The presentation showed off the expanded control that I wanted to add had I been smarter in handling the end of the semester. The slides of the presentation can be seen below.

I then had an idea to at least have some fun with the presentation. Although I couldn’t implement true OSC controls, I could maybe try to fake some kind of physically controlled game by having people mime out actions and then use the controller and keyboard to make the actions happen in the game!

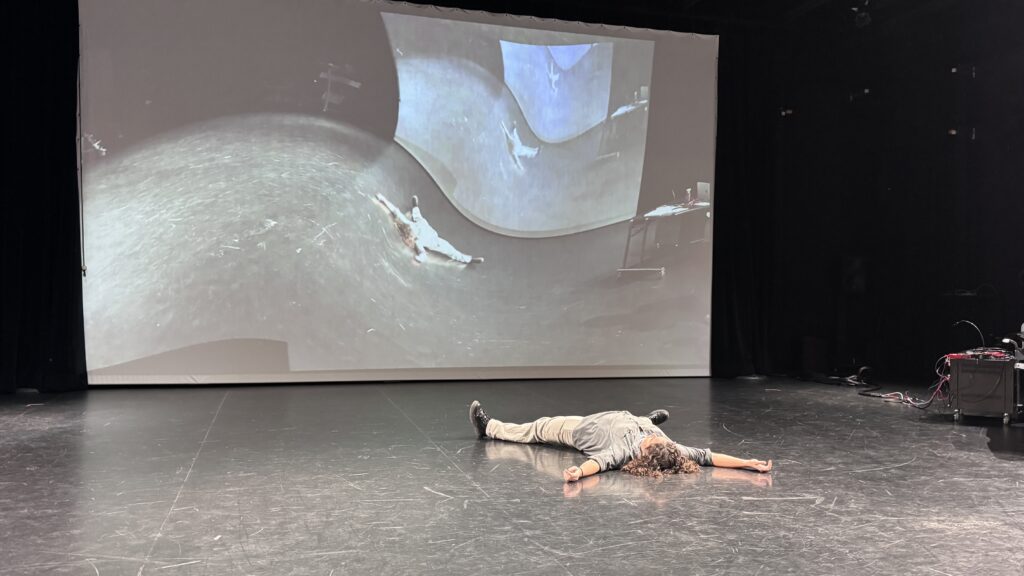

To my surprise, this actually worked really well! I had two people control the direction of the ship and shield by pointing with their arms, and one person in the middle control the vertical position of the ship with their body. I actually originally was going to have the person controlling the vertical position just point forward and backwards like the other two people, but Alex thought it would be more fun to physically run forwards and backwards. I’m glad he suggested this as it worked great! I used the controller which had the ship and shield direction, and someone else was on the laptop controlling the vertical position. The two of us would watch the people trying to control the ship with their bodies and tried to mimic them in game as accurately as we could. A view of the game as it was being played can be seen below.

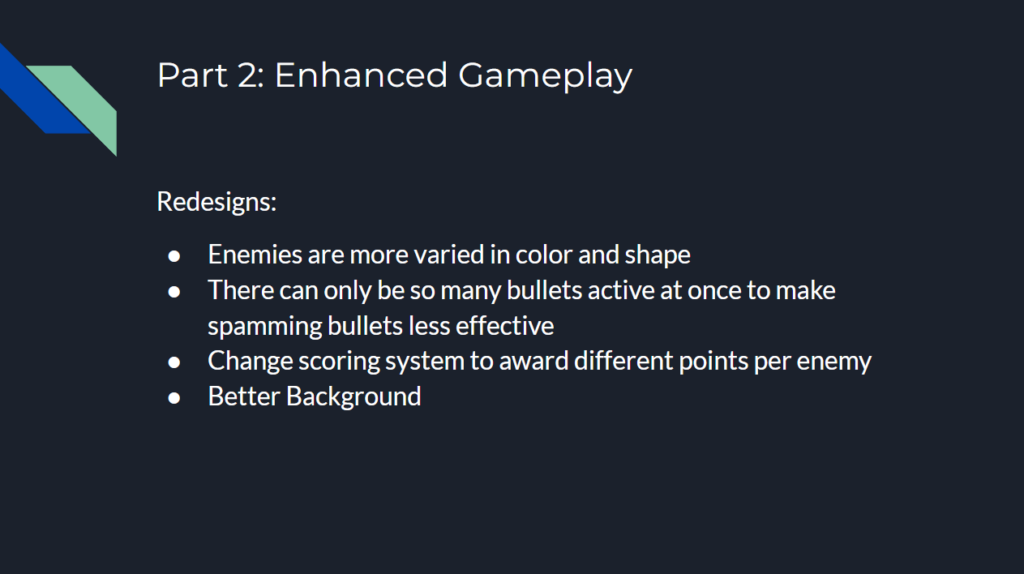

I think everyone had fun participating to a degree although there was one major flaw. I originally had someone yell “shoot!” or “pew!” whenever they wanted a bullet to fire, but this ended up turning into one person just saying the command constantly and it didn’t add much of anything to the experience. I did originally have plans that would have helped in this aspect. For example, I was going to make it so there could only be 2 or 3 bullets on screen at once to make spamming them less effective, or maybe have a longer cooldown on missed shots.

In the end, I had a very good time making this game and I learned a lot in the process. Some of which was design wise but a lot was also planning and time estimating as well!

Cycle 3 – A Taste of Honey

Posted: December 18, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »For Cycle 3, I focused on improving the parts of my Cycle 2 that needed reframing. I started with buying a new bottle of honey so it wouldn’t take long for it to reach my mouth.

Product placement below is for documentation purposes. Not sponsored! :)) (Though I’m open for sponsorships.)

I edited the sound design, making the part of the song Honey by Kehlani that says “I like my girls just like I like my honey, sweet.” play 3 times so the lyrics wouldn’t be missed. In my cycle 2, the button that said “Dip me in honey and throw me to the lesbians” were missed by the experiencers. To make sure it catches attention, I colored it with yellow highlighter. To clarify and better explain the roles of the people holding the honey bottle and the book, I recorded a video of myself, trying to sound AI-like without the natural intonations in my regular speaking voice. I gave clear directions for two volunteers, named person 1 and person 2, inviting them into the space and telling them to do certain things in certain actions in my pre-recorded video. I also put two clean spoons in front of them, telling them that they could taste the honey if they wish. Both people tasted the honey and one of them started talking about personal connections with honey as the other joined. This conversation invited me to improvise within my score where is was structured enough due to having expected outcomes but fluid enough to be flexible along the way to accomplish the score. The choreography I composed didn’t happen the way I envisioned to happen and the experiencers didn’t end up completing the circuit to make the MakeyMakey trigger my Isadora patch. So I improvised and triggered the patch myself. This made the honey video appear on top of the swirly live video affected by the OSC in my pocket. I moved in changing angles and off-balances like I did in Cycle 2, with the recording of my noise effects also playing in the background.

I finished with dropping on the floor, and reaching the 7 women expressing one by one that they are lesbians.

My vision manifested much more clearly this time with the refinements. Though it was funny and unfortunate that the circuit wasn’t completed because the highlighted section of the book attracted to my attention that the instructions I wrote above it ended up being missed, which is a reversal of what happened in Cycle 2. I received feedback that the experience shifted through different modes of being a participant and observer, and shifting emotions between anticipation, anxiety and delight. The responses were affirming and encouraging, making me want to attempt Cycle 4 even outside the scope of this class. Throughout all 3 of my cycles and my pressure projects, I gained new useful skills to use in my larger research ideas. Besides the information on and space for interacting with technology, I am also very grateful for Alex, Michael, Rufus and my wonderful classmates Chris and Dee for creating a generative, meaningful, insightful and safe space that allowed me to not hold back on my ideas!

Cycle 2 – I Like My Girls Just Like I Like My Honey

Posted: December 18, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »For Cycle 2, I was more interested in going after my draft score I initially prepared for Cycle 3 rather than Cycle 2, so I followed my instinct and did not go through with my Cycle 2 draft score.

Below was my draft score for Cycle 3, which ended up being Cycle 2:

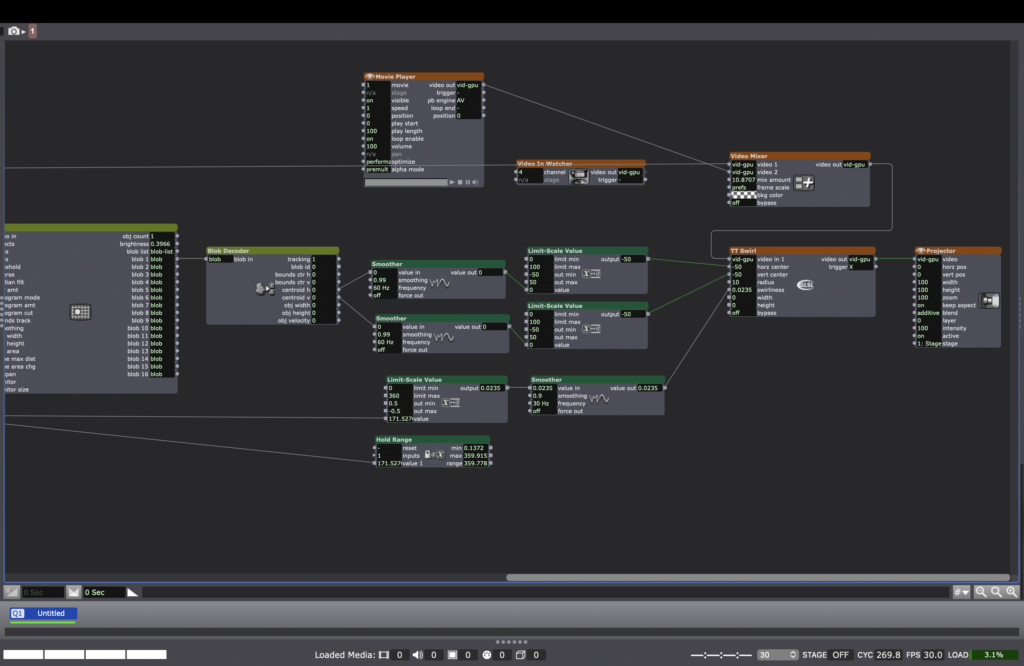

This was going to be the first time I would independently use OSC so I needed practice and experimentation.

We connected an OSC listener to the patch and this way the swirl had the ability to speak to a phone with OSC and respond to it in real time. I put the phone in my pocket and let the movement of my body affect the phone’s orientation, affecting OSC, affecting the projected live video.

After being introduced to this tool, the external tools I needed to acquire to manifest my ideas into action were completed. My Cycle 1 carried heavy emotions within its world-making. I wanted my Cycle 2 to have a more positive tone. I flipped through the pages of my Color Me Queer coloring book to find something I could respond to. I saw a text in the book that said “Dip me in honey and throw me to the lesbians.” With my newfound liberation and desire to be experimental, I decided to make that prompt happen. I connected one end of a MakeyMakey cable to the conductive drawing on my coloring book in the page with this prompt. I connected the other end of a MakeyMakey cable to a paper I attached to the top of a honey bottle cap. This way it became possible for the honey bottle to open and the button on the coloring book to be pressed at the same time, triggering a video in Isadora. I found a video of honey dripping and layered it on top of the live video with the Swirl effect. I also included a part of the song Honey by Kehlani to the soundscape, which said “I like my girls just like I like my honey, sweet.” After those lyrics, I walked near the honey, grabbed it and tried to pour it in my mouth from the bottle. Because there wasn’t much honey left, it took a long time for it to reach my mouth. After I finally had honey in my mouth, I began moving in the space with my phone controlling the OSC in my pocket. It appeared like I was swirling through honey. I also recorded and used my own voice, making sound effects that went with the swirling actions, while also saying “Where are you?” Finally, I dropped my body on the floor, being thrown to the lesbians as a video of 7 women saying “I am a lesbian” one by one.

Due to the sound design and how I framed the experience, I got feedback that some of the elements I aimed for didn’t land fully. When I explained my intention, there were a-ha moments and great suggestions for Cycle 3. Even though I left Cyle 2 with room for improvement, I became ecstatic about having learned how to use OSC. Following this excitement, I decided to use the concepts I included in my Cycle 1 and Cycle 2 in a new-renewed-combined version in my 2nd year MFA showing before my Cycle 3.

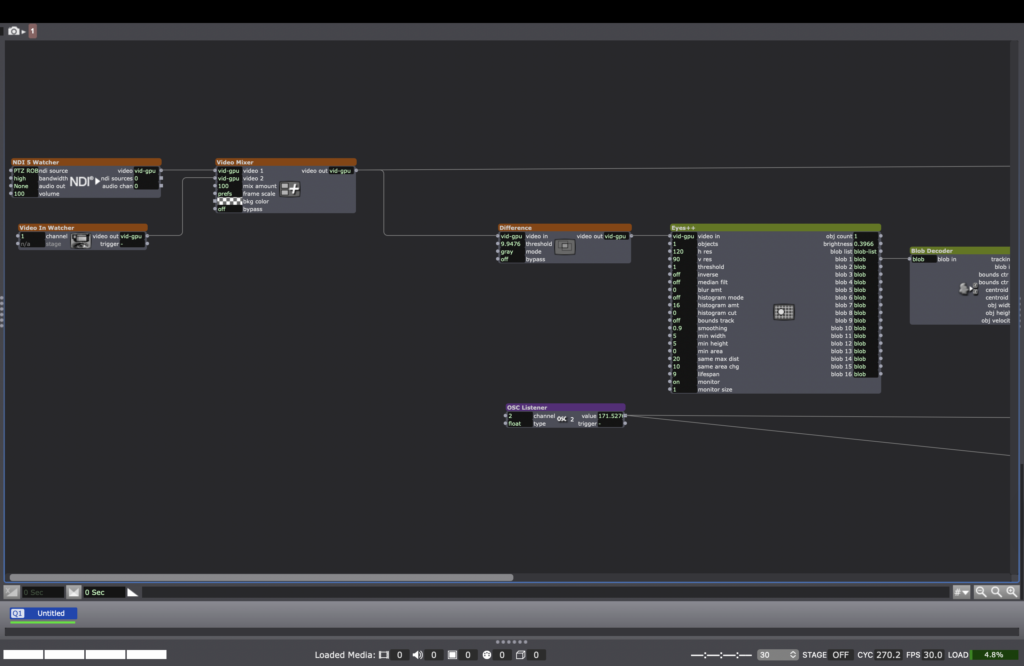

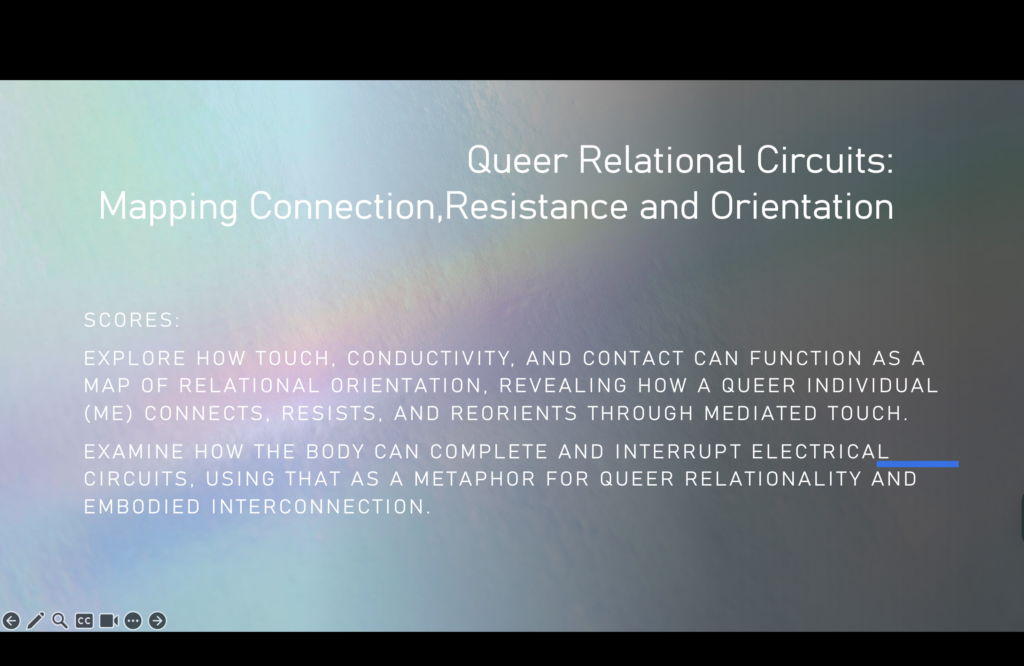

Cycle 1 – Queer Relational Circuits

Posted: December 18, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »For my cycles, I wanted to engage in play/exploration within my larger research interests in my MFA in Dance. My research includes a queer lens to creative expressions, and I find it very exciting to reach creative expressions through media systems and intermedia in addition to movement.

This was my draft score for Cycle 1:

A few days before this cycle, I had just recently bought a new coloring book without plannig of using it for any of my assignments.

The book includes blank drawings for coloring, questions, phrases, journal prompts, and some information on queer history. While flipping through its pages, I remembered that I could use the conductive pencil of MakeyMakey to attach the cable to the paper and make it trigger something in Isadora. So I programmed a simple patch with videos that would get triggered in response to me touching the page in the area where I drew a shape with the conductive pencil and or any other conductive material.

The sections of the book that I wanted to use were: “What is your favorite coming out story?” and Where is your rage? Act up!” I re-found videos on the internet that I had previous knowledge about, which corresponded to the questions I chose. I remembered being younger and watching a very emotional coming out video of one of the Youtubers who I frequently watched at the time. I remember it affecting me emotionally. I wanted to include her video. As a response for “Where is your rage? Act up!’ I remembered found a video of police being violent toward the public at a pride event in Turkey, where I’m from. As a queer-identifying person who was born and raised in Turkey, I was exposed to the inhumane behavior of the police toward people at Pride events, trying to stop Pride marches. This is one instance I feel rage so I included a video of an instance that happened some years ago.

In my possession, I also had a notebook entitled The Gay Agenda, which I had never used before. I thought this cycle was a good excuse to use it so I wrote curated diary pages for this cycle. I also drew on it with my conductive pencil so I could turn the page into a keyboard and activate a video by touching it.

These photos show my setup while presenting:

I used an NDI camera to capture my live hand movements, tapping on the pages, and triggering the videos to appear on the projection. The live video was connected to the TV and the pre-recorded videos were connected to the main screen. I also used a pair of scissors as a conductive material and as symbolism. I received emotional and empathetic responses as feedback, as what I shared ended up journeying me and the audience through a wave of emotions and thoughts. I also received feedback about how my hand movements made the experience very embodied, in response to my question of “I am in the Dance Department, if I use this in my research, how will I make it embodied?” Receiving encouragement and emotional resonance about where I was headed with my cycle allowed me to make liberated and honest choices. Spoiler alert: When starting Cycle 1, I did not know that I was also beginning to plant the seeds to use this idea in my MFA research showing.

Cycle 2: Space Shooter Expanded

Posted: December 18, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »I originally planned to implement phone OSC controls into my Cycle 1 Unity game for this cycle. I would then use the final cycle to refine the gameplay and expand the physical aspects of the controls. Holding a phone is pretty boring, but imagine holding a cardboard shield with a phone attached to it!

However, I realized after some testing that I would need to do some slight gameplay reworks first. This was because after I saw the projection capabilities of the motion lab, I learned that the amount of area that can be covered is severely limited. This is especially true in the vertical direction. After seeing this, I decided to change the way enemies are spawned in. Instead of appearing in a circle around the player, they would appear at the horizontal edges of the screen. Given the size of the projection, I think this will be easier on the player. It still felt limiting in a way though, so I decided to allow the player to move vertically up and down as well.

These were significant changes, so I needed to redesign the game first before adding the phone OSC elements. While going through this process, I added a few new things as well. The overview of changes is as follows:

1. Enemy Spawner

The Enemy Spawner was changed to spawn enemies at the horizontal edges of the screen. This is actually much simpler than the circle spawning it was doing before

2. Player

The Player was given the ability to move up and down on the screen. This means the player class now has to look for more inputs the user can give. There is another consideration though, and that is that the player cannot be allowed to move off screen. To stop this, a check is done on what the player’s next position is calculated to be. If this position is outside the allowed range, the position is not actually updated.

3. Enemies

After implementing player movement, I discovered a major issue. The player can just move away from enemies to avoid them! This trivializes the game in many aspects, so a solution was needed. I decided to have enemies constantly look towards the player’s position. This worked exactly as expected. I decided to make enemy projectiles not track the player however, as this created additional complexity the people playing the game would have to account for.

4. New Enemy: Asteroid

Sense all enemies track the player now, I thought a good new enemy type would be one that didn’t. This new enemy type is brown instead of red and cannot be destroyed by player bullets. The only way to avoid it is to move the ship out of the way. To facilitate this gameplay, when an Asteroid enemy is spawned, it heads towards where the player is in that moment. This also ensures the player cannot be completely still the entire game.

5. Shoot Speed Powerup

After the recommendations I received from the Cycle 1 presentation, I decided to add a powerup to the game. This object acts similar to the projectile objects, in that it just travels forward for a set time. Except when it collides with the player ship, it lowers the cooldown between shots. This allows the player to shoot faster. This powerup only travels horizontally, again to add more variety to object movement.

The final result for this cycle can be seen below.

After finishing the game, I got a great idea. I remembered back to people attempting to play the game for cycle 1, and many of them found it overwhelming to control the ship direction and shield direction. But this new version of the game added an entirely new movement direction! That’s when I decided to turn my project from a single player experience to a multiplayer experience. I would have one person control the vertical movement of the ship on the keyboard, one person hold the left side of the controller to use the left joystick, and one person hold the right side of the controller to use the right joystick and trigger. This way, each person only really has one task and thus it should be a lot easier to keep track of.

However, once I tested this I ran into a major issue. The keyboard and controller could not move the ship simultaneously. It seemed like control was being passed between either keyboard and controller, and so they couldn’t happen at the same time as was needed to control the ship. After much testing, I found that if I had two input listeners, one for each type of user input, simultaneous control could be achieved!

I was running out of time for this cycle, and given the major reworks I made to the game, I decided to push phone OSC controls to the next cycle.

After presenting the game and having the class play it, I received very positive feedback! Most people liked how much easier it was to play when the tasks were divided up. The team effort also allowed them to achieve much higher scores than they were able to get for cycle 1. Two people holding one controller was a little awkward though, and the phone OSC would help with that. Ideally, it should feel like they are all part of a team that is controlling a single spaceship.

PP3 – You are now this door’s emergency contact.

Posted: December 18, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »Our Pressure Project 3 came with a pleasant surprise.

PP3: A Secret is Revealed. Your task is to create a experiental system that has a secret that a user(s) can reveal. Perhaps something delightful or something shocking.

Required resources:

Isadora, A MakeyMakey

Excluded resources: Keyboard & Mouse.

You may use up to 8 hours.

I lit up with joy to read that our Pressure Project included a MakeyMakey. Since being introduced to it by our course instructor Alex, MakeyMakey became a tool that I started excitedly explaining to anybody who listened. With this delight, I wanted to create something that would reflect my sense of humor within this experiential media system.

I created a system where one person would be interacting with it at a time. To complete the circuit that would make the MakeyMakey work as a keyboard, I needed the user to hold one of the cables throughout the experience. But I was also designing this experience with a handwriting component. To facilitate ease and flow of the experience, I needed the user’s dominant hand to be available to write.

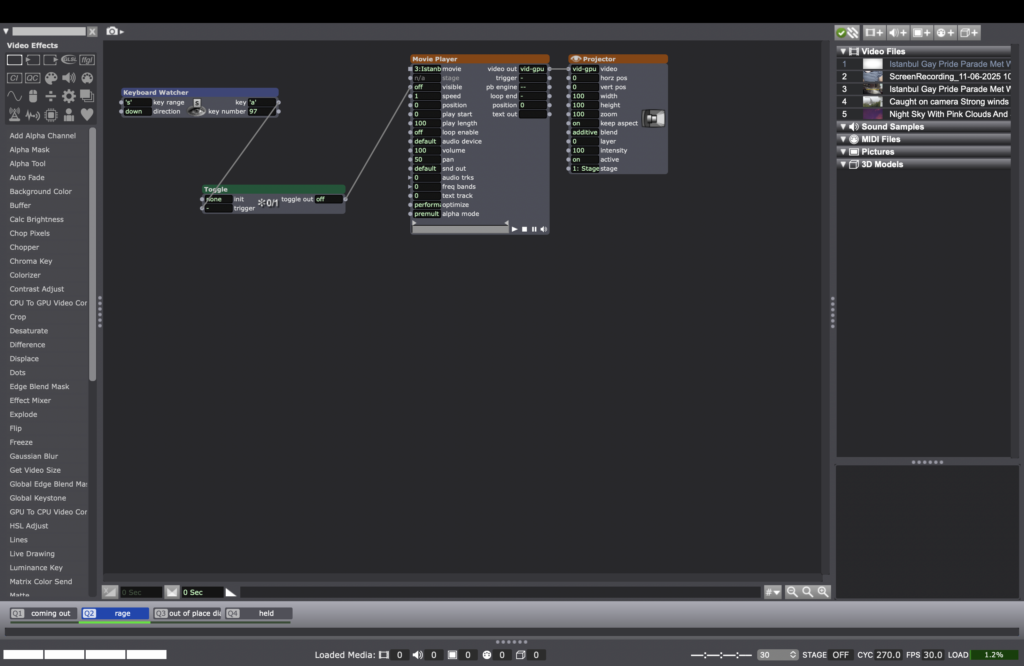

The other end of the cable needed to be connected to something that would complete MakeyMakey’s circuit. I was interested in creating the experience as a ‘journey’, ‘a travel’, ‘a passage’, so I decided to work with images three different doors that would lead the user to three different outcomes without them knowing what comes next. With this door concept, I thought, what better way to complete the circuit with a key that they would need to touch to interact with the doors, so I connected one of the cables of the MakeyMakey to a key. I programmed an Isadora patch where scenes would be triggered with a Keyboard Watcher. Because my computer thought that I would be pressing a button on my keyboard when the MakeyMakey was connected to it, my key became my KEYboard.

In devising this experience, I also wanted an analog part that would make the experience feel more realistic. I prepared and placed 3 papers on top of each other in front of the user. The first one was an image of a fingerprint, which the user would be prompted by the door on the screen to touch. There was no automated connection between the paper and the screen but the user did not know that.

When the user touched the key to confirm, Isadora went to the next scene in my patch.

My system did not actually record the user’s or anybody else’s fingerprint to its database. But with the confusion and hesitation of a user’s thought process in encountering this “Wait I really did press my thumb there. What is happening?” mixes with the silliness of the “Very Important Finger” text.

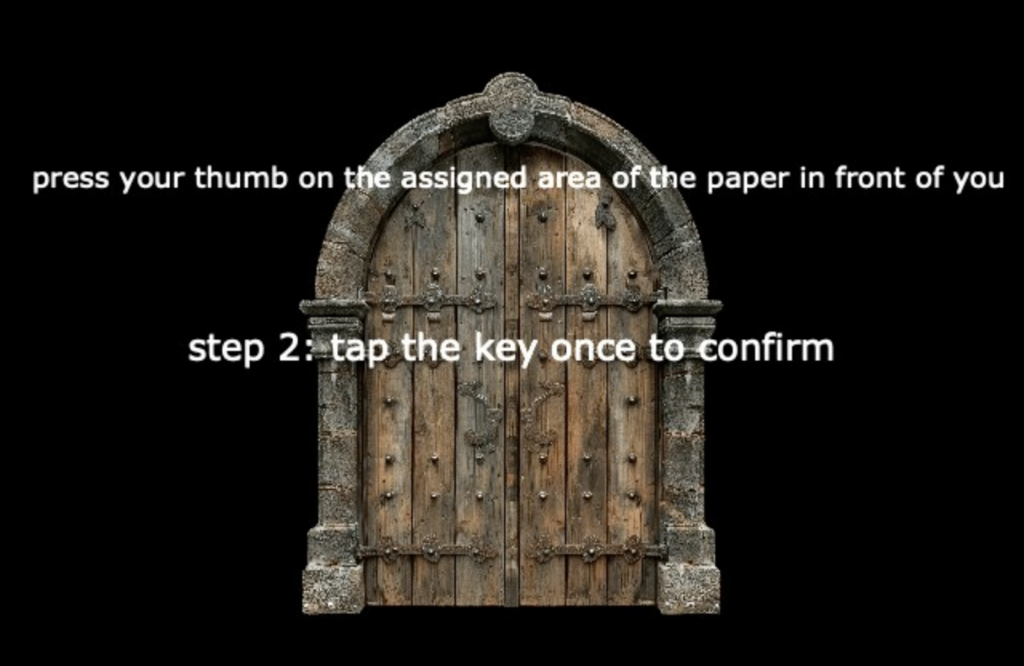

Once their fingerprint has been successfully confirmed, another door (another scene in my Isadora patch) appears. The second page mentioned in this scene is the form below:

Once the user fills out the form manually and presses “Submit Form” which doesn’t trigger anything on my patch but affects the user’s experience, the user touches the key that triggers the next scene on my patch.

Secrets kept getting revealed as the user kept interacting with the system with their personal information that leads to unexpected outcomes – which I found delightful.

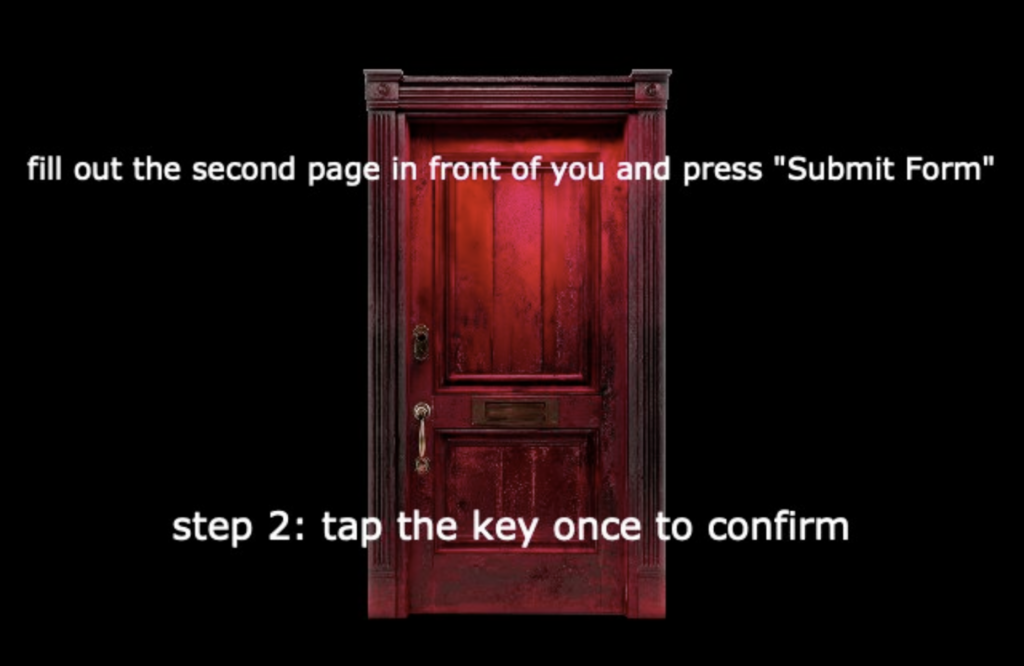

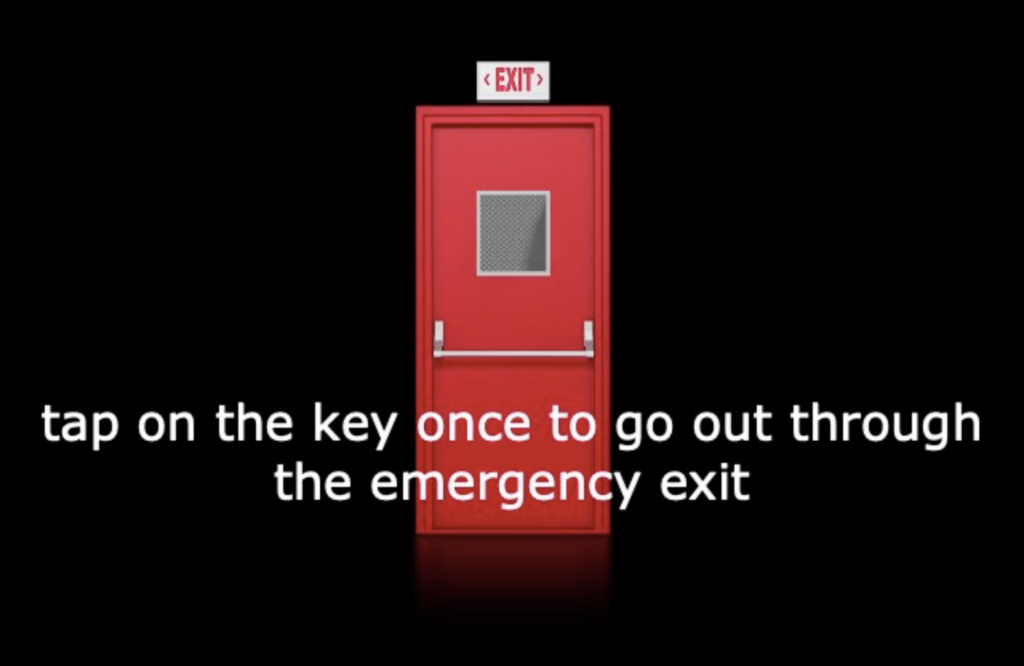

After filling out the Emergency Contact Form, my patch leads the user to an Emergency Exit which merges meanings between the previous and the current action but not in a congruent manner.

Since this experience was experienced at an academic setting, I assumed this scene would be relatable to any user in the space, keeping the personal information gathering (nothing is being gathered but the user does not know that), but now at a psychological level.

The third physical paper in front of the user is the image below:

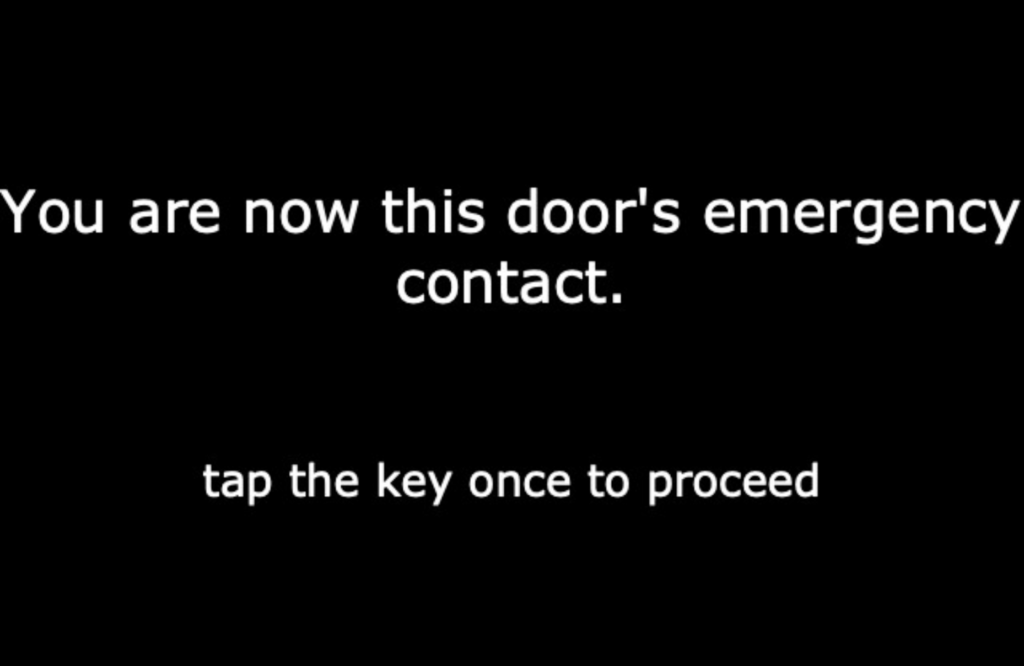

Once the user presses the icon and taps on the key to confirm, next scene appears in my patch:

The last scene in my patch is a video of someone setting a computer on fire, which is my suggested method of cleaning the user’s inbox in this experience.

Designing and devising this experience was a delight for me but the most delightful part was watching the user interact with my system. I couldn’t help but giggle as the scenes unfolded and the user cooperated with each prompt.

While presenting this project, we also had visitors in our classroom who did not know the scope of the DEMS class. They also did not know MakeyMakey or Isadora. They observed as my classmate who knew the scope interacted with the system. Their questions were meaningful and unbiased, trying to understand what the connection was and how it worked. On our feedback time I also received a comment about my giggles and excited/happy bodily expressions affecting what the experience was for the other people in the room, which felt like a natural extension of how joyfully the experience of devising this experience began for me. Doing the programming part gives me tools to work with but what I also find very generative and useful for my creative work as an artist is devising the experience “around” the technology, creating other elements of the experience that complement/support/add to what the technology does.

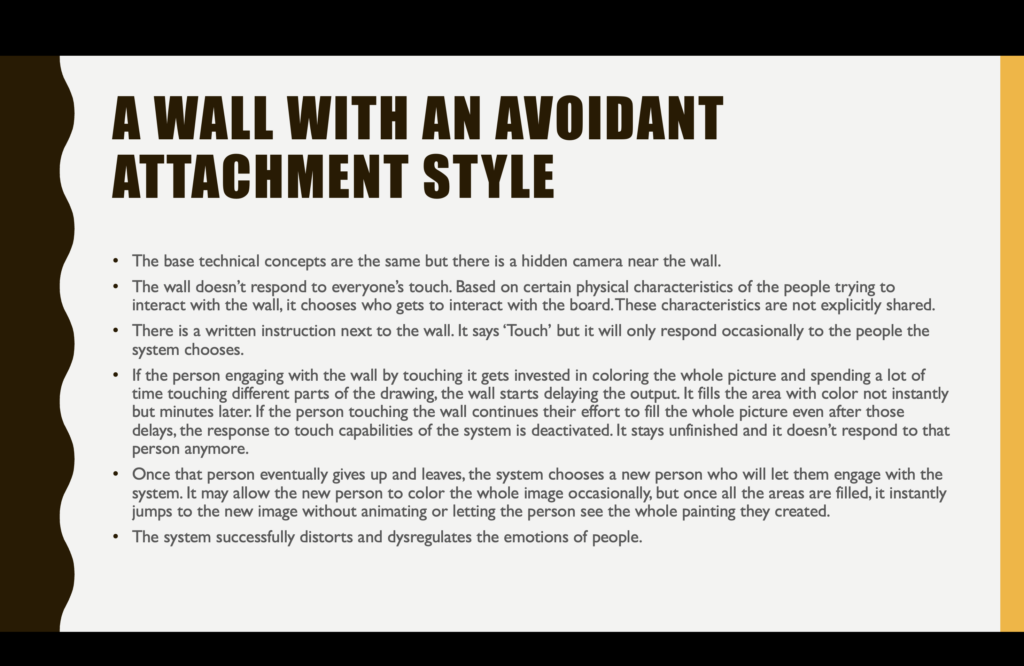

PP2 – A WALL WITH AN AVOIDANT ATTACHMENT STYLE

Posted: December 18, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »For our Pressure Project 2, our task was to go to place where people are interacting with an automated computer system of some sort, spend time observing how people interact with the system and how the system makes people feel. After documenting the system with diagrams and pictures, we were asked to put on your director’s hat and re-design/iterate the system so that it is “better” or “more nefarious”. The day this pressure project was assigned, I knew that I wanted to re-design a system to be more nefarious before choosing what system I would interact with because as an artist I felt more interested in the playful creativity aspect rather than the functionality aspect.

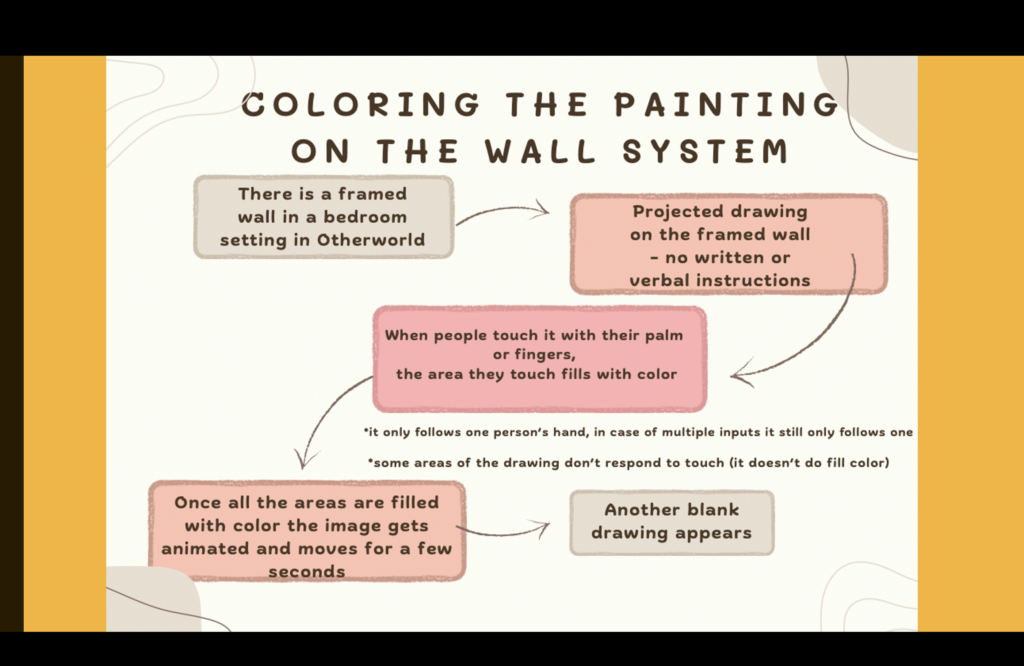

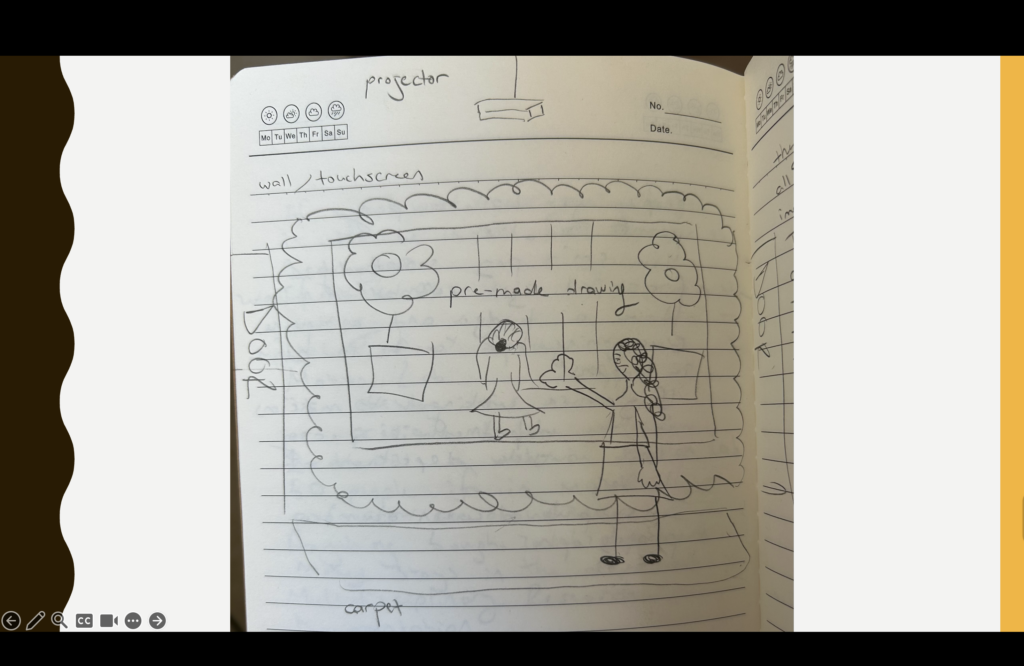

To begin my quest, I went to Otherworld, the immersive art installation in Columbus, by myself. There were many different and interesting rooms and stations with many automated computer systems. In choosing which one I would use for my project, I had two criteria in mind. It needed to spark my interest and it would need to be an area where I could stay for a long period of time to observe. While wandering around enjoying the installations, I found myself lingering in a room, instinctively beginning to observe how people interact with it. It didn’t have a title but I named it Coloring the Painting on the Wall System.

I did a quick (and obviously very aesthetically pleasing) drawing of the system and the surrounding setting.

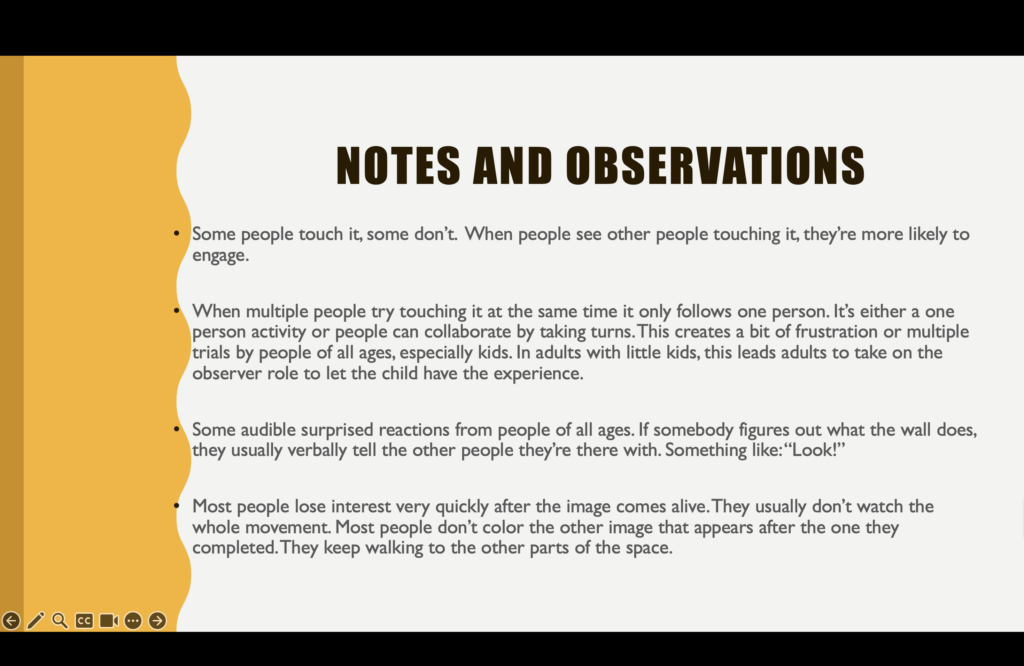

I’m sharing some of my notes and observations about how people interacted with it.

After documenting my observations in my notebook, I continued my stroll around the installations, interacting with various systems in the space. Because I already spent time observing how people interact with one system, I found that I became more attuned to how people interacted with the other systems in the space as well. As a dancer, I often find myself more kinesthetically engaged with automated computer systems. In this space, I also had the opportunity to observe people engaging through other modes.

After my field trip, I moved on to the next exciting part of the assignment. How could I make this more nefarious?

This question came with an additional question of what nefarious meant for me and how I would define and express it experientially. Around the time of this Pressure Project 2, I was going through a particular experience in my personal life, not understanding why someone was behaving the way they were. Their actions felt nefarious in response to how I was trying to interact with their nervous “system”. So I decided to translate my frustration with their nervous system into an automated computer system.

Inspired by a conflict, creating “A Wall With an Avoidant Attachment Style” made me transform resentment into humor, and realize even more that even small changes in timing and responsiveness of automated computer systems hold the capacity to change the experience of the user drastically. While I hope no one would need to interact with “A Wall With an Avoidant Attachment Style”, I do think that in re-designing the qualities of the system, I got a better understanding of how automation and emotion intersect. This is an aspect I can meaningfully use in other designs now, whether nefariously or not.

Cycle 1: Space Shooter

Posted: December 17, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »I knew that the interactive system I wanted to make for the cycle project was some kind of video game using Unity. I also knew that I wanted it to be a simple 2D shooter game where the player controls a ship of some kind and fires bullets at enemies. However, because this class is about interesting ways you can interact with systems, I thought using a controller would be boring! My initial plan was to use the top-down camera in the motion lab to track the player’s movement. This would turn the player’s body into the controller. Then, instead of a standard screen being used, the gameplay would be projected onto the floor. That way it was almost like the player was in the game, without having to use any VR! The game would have looked something like the classic game Space Invaders, shown below.

My plan was to have the person controlling the ship have a light on their head and another light they can activate. The camera would use the light on their head to track their movement and the activated light to fire a bullet. I realized there was likely a major flaw with this design though, and that was that the camera in the motion lab does not have a big enough view to accommodate the space I wanted. I also hadn’t considered the role that perspective would play on the camera. This made me move away from Space Invaders and more to a game like Asteroids, shown below.

The idea is to lock the player in the center of the screen so that the person controlling the ship can stand directly under the camera. This makes the camera angle less of an issue while still allowing the person to control the direction the ship is facing with their body. An additional interesting result of this is that the person in control cannot see behind themself like you could watching a screen of the entire game, which adds an additional interesting layer to the gameplay. Because the ship loses the horizontal movement seen in Space Invaders, I decided to add a shield mechanic to the game as well. The idea is that some enemies would shoot projectiles at you that you cannot destroy with bullets and must block with a shield. The person controlling the ship would use one arm to shoot bullets and one arms to block projectiles.

With that in mind, my goal for this cycle was to create the game working on a controller. The two joysticks would control the ship and shield direction and the right trigger would fire bullets. There would be two enemy types: One that is small and fast, and one that is bigger, slower, and can fire projectiles.

The main Unity scripts made were:

1. Player

2. Player Projectile

3. Shield

4. Enemy

5. Enemy Projectile

6. Enemy Spawner

7. Game Manager

I don’t want this post to just turn into a code review, but I’ll still briefly cover the decisions I made with these scripts.

1. Player

The Player checks for user input and then does the following actions when detected:

– set ship direction

– set shield direction

– spawn Player Projectile (the Player also plays the projectile fired audio clip at the same time)

2. Player Projectile

The Player Projectile moves forward until it either collides with an enemy or a timer runs out. The timer is important as otherwise the projectile could stay loaded forever and take up resources (memory leak). If the projectile collides with an enemy, it destroys both the enemy and the projectile.

3. Shield

The Shield is given its angle by the Player. It does not check for collision itself, the Enemy Projectile does that.

4. Enemy

The Enemy is actually very similar to the Player Projectile, it moves forward until it either collides with the player or a timer runs out. If the enemy collides with the player, it destroys the player which ends the game. There is also a variant of the Enemy that spawns Enemy Projectiles at set intervals.

5. Enemy Projectile

Similar to the Player Projectile, the Enemy Projectile moves forward until it either collides with the player or a timer runs out. If the projectile collides with the player, it destroys the player which ends the game. If the projectile collides with the shield, it destroys itself and the game continues (nothing happens to shield).

6. Enemy Spawner

The Enemy Spawn is what spawns enemies. Because enemies just move forward, this script calculates the angle between a random spawn point and the player and then spawns an enemy with that angle. The spawn points is a circle around the player. Every time an enemy is spawns, the time between enemy spawns is decreased (i.e. enemies will spawn faster and faster as the game progresses).

7. Game Manager

The Game Manager displays the current score (number of enemies defeated) as well as plays the destroy sound effect. When an enemy is destroyed, the interaction calls to the Game Manager to track the score and play the noise. When the player is destroyed, the interaction calls to the Game Manager to play the noise and display that the game is over.

The final game result for this cycle can be seen below.

Some additional notes:

The music is another element in the scene but all it does is play music so it’s pretty simple.

The ship is actually a diamond taken from a free asset pack on the Unity Asset Store. Link

The sound effects and background music were also found free on the Unity Asset Store. Because of the simplicity of the game, retro sounds made the most sense. Sound Link Music Link

Just after the entire game was done, I closed and reopened Unity and all collision detection was broken! I ended up spending hours trying to figure out why before creating an entirely new project and copying all the files over. So annoying!

After presenting to the class, I was initially surprised at how much some people struggled with the game. I knew it was difficult to keep track of both the ship and the shield using the two joysticks, but I didn’t consider how nearly impossible this was for people who had never used a controller. Otherwise, the reaction was fairly positive. One note that makes sense was to possibly try to differentiate between the two enemies clearer as they are the same exact color and that can be confusing. There were also some cool suggestions such as adding powerups to the game. It was also suggested that maybe instead of trying camera tracking, I could use phone OSC to have the players control the ship instead. This seemed like a much better idea and so I decided to investigate that for the next cycles.

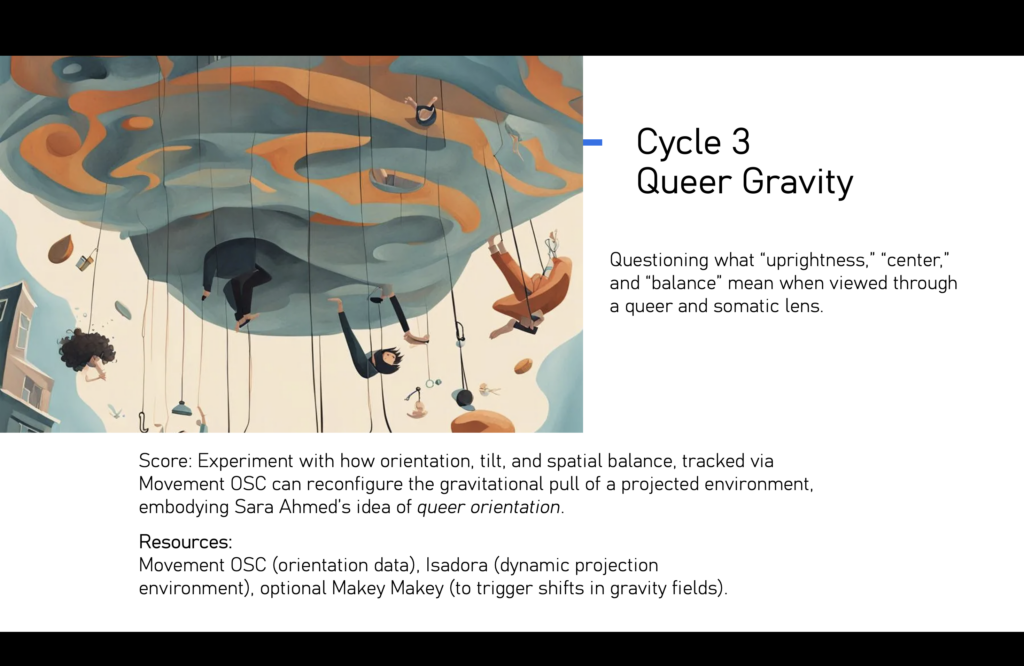

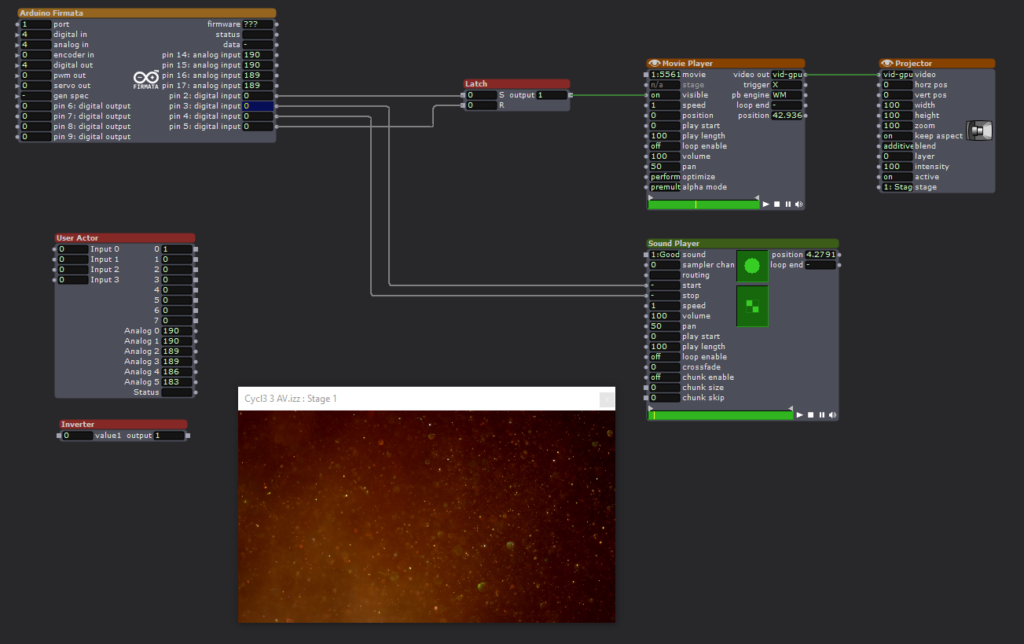

Cycle 3

Posted: December 15, 2025 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »I somehow managed to get through cycles 1-2 without actually doing anything with Isadora or other technology. Although I learned a lot, I needed to include the “MES” in DEMS. And what a mes I made!

Perhaps the mist valuable topic explored in my Cycle 2 was the part about proximity. What is the distance between a users actions and the result of that action? Is it immediate like a typewriter, or further away like a garage door opener? Cycle 2 focused on proximity from the point of view of the user, but what about from the perspective of the tech itself? What is the user is unaware that they are interacting with technology at all? This is what Cycle 3 explored. How does a machine detect its own proximity to a user.

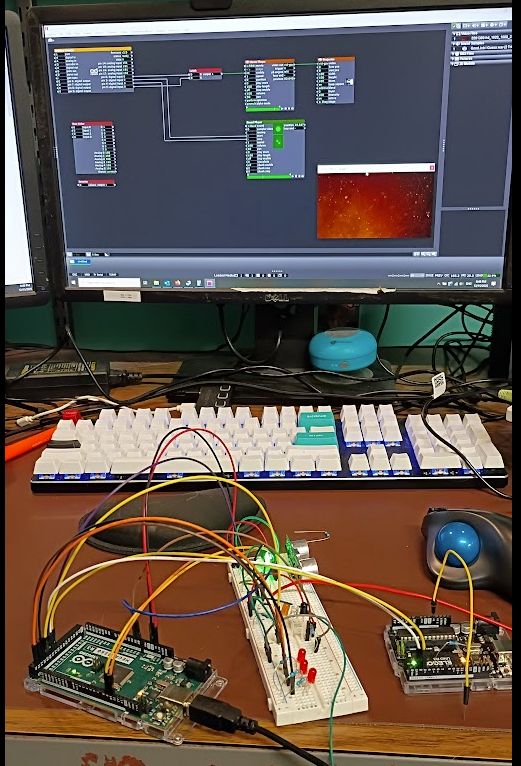

For this project I chose three technologies to explore, as shown above. First (left) is an ultrasonic sensor. It broadcasts an ultrasonic sound and listens for the returning echo. It is capable of detecting something within range as well as the distance the object is form the sensor. Second (center) is Infrared optical sensing. These are commonplace pieces of tech used to detect the presence of objects. A transmitter (clear LED) emits an IR beam of light. The receiver (black LED) detects the IR beam. If the path between the transmitter and detector is broken, the presence of an interfering object is detected. This is what usually prevents home garage doors form closing if something is in the way. Third (right) is a capacitive sensor. It detects the presence of an object by detecting a change in the state of charge across an electric circuit. See my PP3 for more information about how this works. For my tests I used a piece of copper mesh roughly 11×17 soldered to a length of wire (below). My cats were extremely interested in the mesh and kept triggering the sensor!

Cycle 3 includes two main parts. One, the electronics portion that explores the three sensor types mentioned above. The second piece is exploring how these inputs can be utilized by Isadora.

The photo above (my desk puts the MES in DEMS) shows the results of my efforts. On the left is an Arduino Mega controling the detection circuits and reporting to the PC and the user its status. The white piece in the middle is an electronics breadboard which contains the electrical components for the sensors. On the right is a smaller Arduino UNO loaded with the Firmata program that communicates with Isadora.

The system works by the Arduino Mega and the breadboard detecting the presence of a user then passing that information to the UNO, which then tells Isadora to do something. The Firmata User Actor, and its associated Arduino Firmware is an incredibly powerful and easy to use system that makes the task of getting GPIO in and out of Isadora. However, it does not provide easy means of expanding upon its functionality without essentially rewriting the Firmata software. This is why there is a second arduino, the mega, to handle the custom software needed to drive the detection circuits.

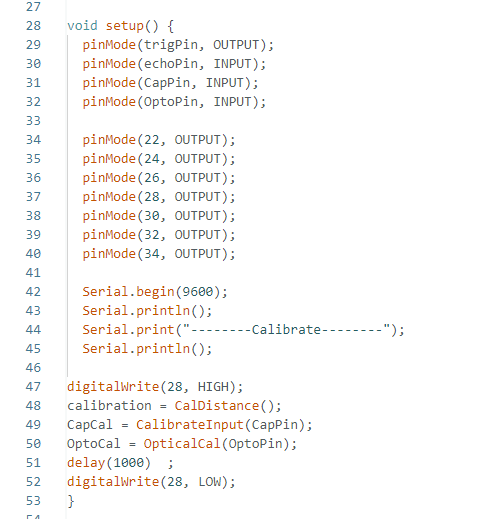

In an Arduino program, called a sketch, the first code that runs in part of a “setup” function. This is what tells the arduino what its ins and outs are as well as running any code that needs to happen before the main program takes over. Above is the code for my project. Lines 47-52 are the main interest here. The sensors require calibration before they can be used. The sensors need to know what the environment is like without the presence of a user so that it can compare that to when a user is nearby. Thus the first major step is to initialize each sensor type. Each sensor takes 10 readings, averages the results, and declares that is the default value. While this is happening an orange LED is illuminated on the breadboard to tell the operator that the system is in this process.

Once this step is completed, the system constantly takes readings from the sensors and compares the values to the calibration data, if the difference exceeds a threshold value a detection is registered. For convince the system also illuminates a red led to let the user know that a detection has occurred, there is a separate LED for each sensor. Here the user is the programmer, not the audience who is being detected. In addition to illuminating an LED to indicate that a sensor has detected something, a message is sent to the Isadora Arduino to let it know that there has been an event.

The Isadora scene is a straightforward affair. The Firmata actor is constantly monitoring the state of the Arduino Uno configured with the Firmata sketch via the Serial Bus. When pin2 goes high, a video is played. When pin3 goes high, an audio clip is played. Pin3 stops the audio. Pin4 resets a latch that keeps the video playing.

When the sensor electronics detects an acoustic trigger, it plays the video. When the optical sensor detects a change it plays the video, a second event stops the audio.

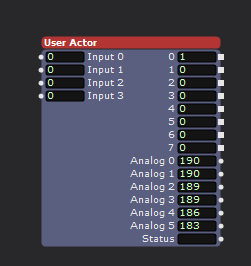

Expanding the Firmata Actor

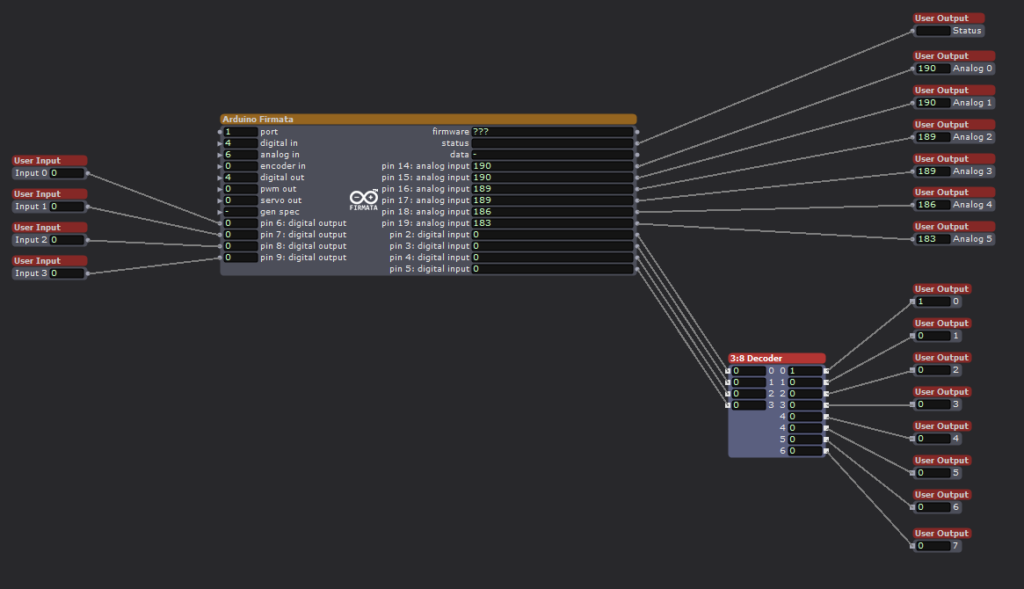

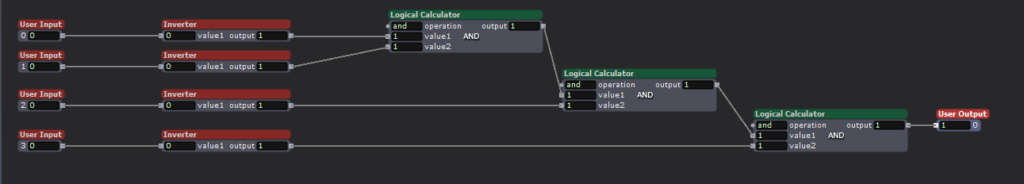

Above is a user actor that utilizes some additional logical processing to increase the number of inputs to Isadora. The Firmata Actor simply observes the digital pins of the connected Arduino to see if their input is either high or low. This is enough capability to implement binary decoding to allow the limited inputs to be expanded. As seen above, the user actor has 8 outputs, but the connected Arduino is only utilizing three of its physical inputs.

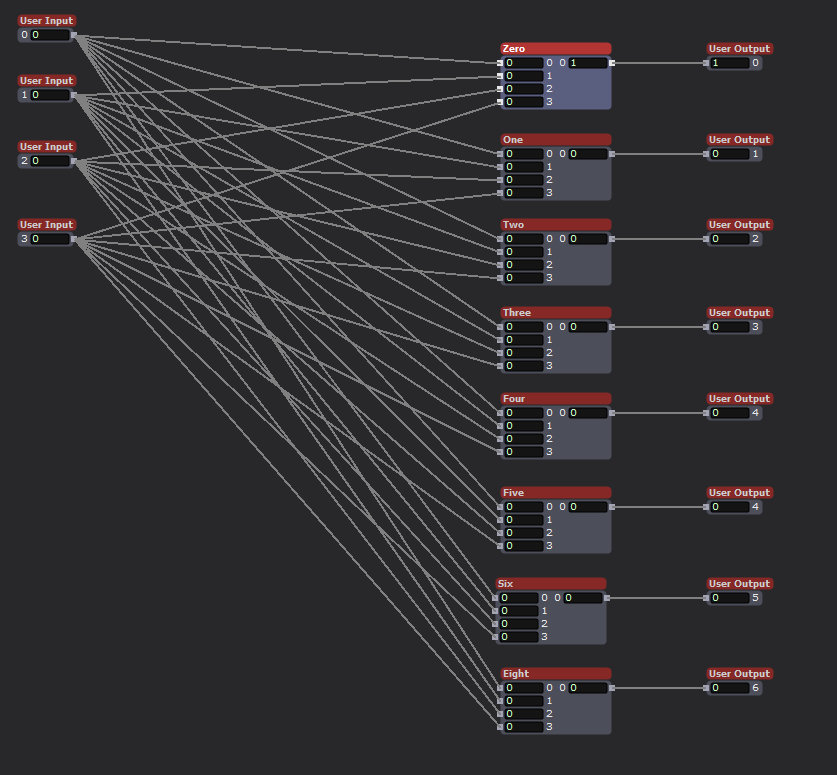

Looking inside the User Actor we can see the Firmata Actor with 4 digital inputs. We are ignoring the analog inputs for this exercise. Although there are four inputs shown, I am only using three of them to achieve 8 binary inputs. Utilizing all 4 physical inputs would allow for 16 binary inputs, but was not implemented here. The technical trick is occurring in the 3:8 Decoder user actor.

Inside the 3:8 Decoder actor we see that the four inputs are connected to 8 modules. These modules are the heart of the system.

Using the Logical Calculator actor is is possible to implement Complementary Digital Logic. If you are interested please look into OSU ECE 2060 and ECE 5020.

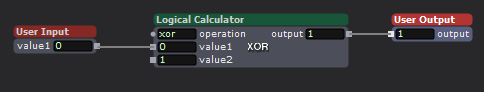

One final user actor was needed first, a digital inverter. This takes an input, either a 0 or 1, and outputs the opposite value. All that is needed is a Logical Calculator actor in XOR mode.

To implement Complementary Digital Logic, it is necessary to have the complement of a logical bit. In this case the opposite value of an input. For example, if Arduino input-1 is HIGH, we also need input-1! (input-1 Bar, or input-1 NOT). This tells the system that an input is NOT currently active. By combining the logical states of the three utilized physical inputs, with AND logical actors it becomes possible to encode additional states, to the value 2^(#inputs).

Currently the Arduino Mega processing the sensor input only has three sensors, but by encoding the status of the sensors it is possible to feed more sensor inputs into Isadora than would normally be possible using the Firmata actor. There are methods for passing serial data into Isadora to achieve even greater input count, but my method is technically simple to implement and is very robust and avoids complications that arise with serial communication protocols.

Putting all of this together for my home DEMS

A key part of my home DEMS is the creation of several secret doors. These are implemented by having sections of a wall sliding away to reveal the passageway. Just like an elevator, it is vital that the doors do not close on anyone (See my PP1, no chomping here). The IR optical sensor will work well for this use case. It is simple and works in a vary direct line of sigh manner. If anything breaks the beam it means that there is an obstruction in the doorway. By monitoring this sensor the door control can know not to close on anyone, or the cats.

What sort of mysterious home would I have without a giant, vaguely threatening, carnivorous plant! Certainly not one worth visiting. It is a goal to have such a character at home. Some type of large carniverous plant, think Audrey but cuter. I want the plant to follow people as they walk past, and if they get close enough I want it to take a chomp at them. This is the perfect place to utilize the ultrasonic sensor. By placing several such sensors around the plant it will be possible to detect the presence of a person as well as knowing how far away they are. With this data the plant can track them and eventually try and take a bite!

The optical and ultrasonic sensors are discrete and the light and sound they produce is undetectable by humans, but they require line of sight to work. Neither can work if they are completely enclosed or obscured. The IR detector is tiny, but does require a hole of some kind for the light to pass through (or an IR transparent window). The capacitive sensor is different, it can be completely hidden. The metal mesh that acts as the sensor can be hidden under carpet, behind a painting, under a tablecloth, even in the fabric of a pillow or cushion. I envision using it to detect when someone enters a room or if they are reaching to grab an object. For example, imagine a crystal ball sitting in the center of a table. By hiding the sensor under a small tablecloth it is possible to detect when someone reaches out to the ball, without actually touching anything. This could trigger some other effect such as the ball glowing or a sound playing.

If nothing else, the sensor made a good cat toy. Biscuit approves (below)! I had to cover it with an empty cereal box to keep them form clawing at it, but then they became very curious about the box! There was no winning.